Table of Contents

Feature Article

Using Kodak Photo CD Technology for Preservation and

Access:

A Guide for Librarians, Archivists, and Curators

Anne R. Kenney and Oya Y. Rieger

Cornell University Library, Department of Preservation and

Conservation

preservation@cornell.edu

Cornell University Library Department of Preservation and Conservation has just published a brochure summarizing the findings of a study to evaluate the use of Kodak Photo CD technology for preserving and making available a range of research materials. Funded by a grant from the New York State Education Department's Program for the Conservation and Preservation of Library Research Materials, the study was conducted in cooperation with the eleven New York State comprehensive research libraries. In addition, six other institutions participated in investigating the applicability of the findings.

The study was inspired by the strong interest in the use of the Kodak Photo CD technology within the cultural community, as the technology offers a commonly available and relatively inexpensive means for creating digital surrogates of research materials. Building on the work undertaken at Cornell on digital capture requirements for text-based materials, the project was designed to evaluate the Photo CD technology by controlling the factors affecting image quality during photography, digitization, and on-screen viewing. The study involved only paper-based documents, and was limited to documents scanned using the basic Kodak Photo CD method (Image Pac). This article aims to summarize the major findings and recommendations of the study. Both the Web and print versions of the brochure include the detailed findings, as well as the description of the study and the methodology used. The Web version of the brochure is available at the department's Web site. To obtain a hard copy of this report, please send a self-addressed, stamped 9x12 envelope (first class postage for a 4.5 ounce brochure - $1.24 for US and $3.80 for overseas) to Mary Arsenault, Department of Preservation and Conservation, 214 Olin Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853.

Key Findings

Finding #1: Kodak Photo CD Technology Is A Viable Means To Digitize Many, But Not All, Categories Of Special Collection Materials For Access Purposes.

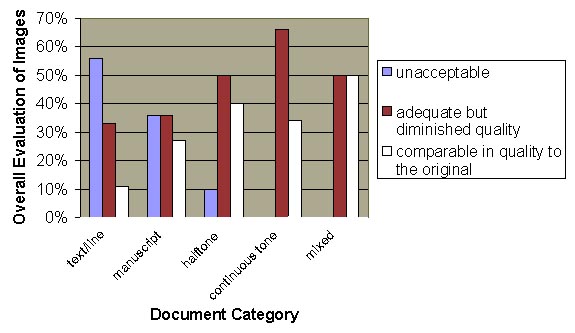

In our study, the participants ranked none of the digital images as providing improved quality over the original documents, but they did find that in 85% of the cases, the Kodak Photo CD images represented acceptable digital surrogates to the originals. Table 1 presents the overall quality evaluations as a percentage breakdown based on document categories. These evaluations are highly subjective; nonetheless, some general conclusions can be derived from them:

Table 1: Overall Evaluation of the Images Included in the Study

Finding #2: Cultural Institutions Should Assess Their Documents' Attributes In Determining Whether Kodak Photo CD Is An Appropriate Choice For Digitization.

Cornell has spent a number of years developing a means for correlating document attributes to digital outcomes, called benchmarking. Benchmarking is a systematic procedure to forecast a likely outcome in using digital imaging for preservation and access purposes. As elaborated in the brochure, the benchmarking approach can be effectively used with the Kodak Photo CD technology to predict whether satisfactory results will be achieved when digitizing a particular document. To determine whether the effective resolution achieved via Kodak Photo CD will be sufficient, the following factors should be considered:

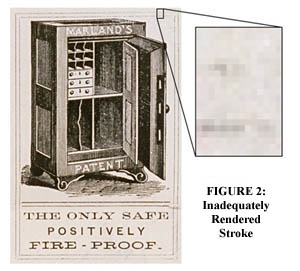

Based on these five factors, Cornell has devised a number of formulas and quality projection tables to assist cultural institutions in determining whether Kodak Photo CD offers sufficient resolution for a particular document type. These recommendations are for benchmarking purposes only to forecast levels of resolution quality that can be achieved via Kodak Photo CD. The formulas and tables presented in the brochure provide a general means for equating the number of pixels (dots) used to a straddle a detail -- or a finest line (stroke). For instance, it was determined that the finest stroke in a document can be rendered with good legibility by a minimum of 1.5 pixels. If less than one pixel is used, the feature will drop out. Figure 1 shows that approximately two pixels adequately rendered the stroke, whereas in Figure 2, the borders of the document were inadequately rendered as there was at most a single pixel straddling the finest line.

higher resolution image |

|

The quality rankings presented in the brochure are conservative because they are meant to be generalizable to a range of document types and to factor in effects of color, density, contrast, generational loss, and the like. For example, it is often difficult to measure and assess detail in photographs because they do not exhibit the same sharpness or crispness as graphic or textual materials. This fact is reflected in project evaluations: reviewers were more critical in evaluating resolution of manuscripts than of photographs where detail rendering is often difficult to assess (see Table 1).

Finding #3: The Best Quality Will Be Obtained Via Kodak Photo CD By Controlling The Steps Of The Digital Process Including Photography And Scanning.

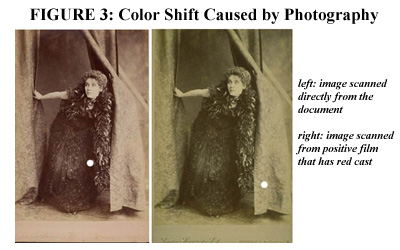

From Source Document to Photographic Intermediate

Because the Photo CD technology does not involve direct scanning

of source material but rather relies on the creation of 35mm slide

intermediates, the photography and film processing can have a large

impact on the quality of digital images. We offer the following

recommendations in controlling the variables associated with

photography to maximize the photographic quality.

Use of Targets

It is highly desirable to include both grayscale and color

targets during photography to provide a level of control over color

and tone shifts. Color and grayscale targets are instrumental in

color-matching images during photography, digitization, on-screen

viewing, and printing. Good color-matching requires not only the

information on the color scale, but also the grayscale control of

shadows, mid-tones, and highlights. We recommend that even for color

documents, you use both color and grayscale targets. Ideally where

possible, these targets should be photographed with the individual

document.

Scanning

The equipment used, its performance, and operator judgment can

have a tremendous impact on determining image quality. In our study,

we had three different scanning technicians, and the results were

slightly different in each case. The brochure includes

recommendations to maximize image quality during scanning, and

outlines a scanner calibration technique based on the use of the

grayscale target captured during photography.

Finding #4: Cultural Institutions Should Carefully Assess The Quality Of Kodak Photo CD Images Produced By Imaging Service Bureaus.

You will want to evaluate images on a number of fronts: overall presentation, detail capture, and color appearance. Image quality assessment can be a subjective process; therefore, we suggest that you control your viewing environment before proceeding with on-screen image quality evaluation. The impact of the image retrieval process on perceived image quality is often underestimated. If retrieved improperly, even a very high quality image may appear unsatisfactory. The factors that affect the perceived image quality on-screen include:

Hardware Configuration

We recommend the following hardware configuration to optimize the

viewing of Photo CD images:

Image Retrieval Software

A variety of freeware and shareware viewing software that support

Photo CD images is available on the Web. To optimize images, we

suggest that you use Adobe Photoshop with the Kodak Photo CD Acquire

Module plug-in to ensure correct mapping of Photo CD colors.

Directions for loading and using this plug-in are provided in the

brochure.

Viewing Conditions

An important prerequisite for viewing images is a controlled

viewing environment. The monitor and the original document need

separate viewing environments. The original is best viewed in a

bright surrounding, and the monitor in a dimmed surrounding. The

brochure includes recommendations in creating an ideal setup.

Monitor Calibration

A common problem when evaluating images is that they may appear

differently when viewed on different monitors. Calibration is the

process of adjusting your monitor's color conversion settings to

standardize the display of images on different monitors. The keys to

calibrating a monitor are to set the gamma and white point. You can

optimize your monitor at the following settings suggested for image

evaluation:

gamma = 2.2

white point = cool white (5000 Kelvin)

color depth = millions of colors (24 bit)

Color Management Systems (CMS)

As described in the

December

15, 1997 issue of RLG DigiNews, one of the main challenges

in digitizing color documents is to maintain color fidelity and

consistency across the digitization chain, including scanning, image

display, and printing. It is important to retrieve the Kodak images

using the Acquire Module plug-in as it takes advantage of the Kodak

Precision Color Management System, and provides a color-managed

conversion to output devices.

Conclusions

This demonstration project led to as many questions as it did to

answers. Additional research could be conducted on the effectiveness

of Kodak Photo CD in digitizing other source materials, such as three

dimensional museum objects or paintings that exhibit overlay, depth,

and translucency characteristics. A logical follow on study might be

to compare the quality, cost, and utility of creating Kodak images

from different sized photo-intermediates, including 4x5 and 120 mm

transparencies. The current project barely touched on issues

associated with printing or Web access, and did not address database,

indexing, and other organizational considerations.

Nonetheless, this project has assisted Cornell in evaluating the use of Kodak Photo CD technology for digitizing special collections materials. Our main conclusions - involving digital benchmarking, ratio of physical size to detail, controlling the digitization chain, optimizing image acquisition and display, and establishing a quality control program - can be found in the brochure, and offer a good starting place for those contemplating a Kodak Photo CD project.

Technical Features

The Promise of DVDs for Digital

Libraries

Steve Gilheany, Archive Builders

SteveGilheany@ArchiveBuilders.com

The compact disc (CD) technology is over fifteen years old, an eternity for things digital. However, the DVD, popularly known as the Digital Video Disc, should soon make the CD obsolete. This new storage medium establishes high standards for digital recording of audio and video, and represents a major advance in storage capacity over CD-ROMs. It will also impose these standards on the personal computer (PC), facilitating the merger of PCs with televisions and VCRs. Because of the DVD, PCs will be ready for quality Internet video broadcasts when multi-megabit per second local loop connections become available at the same price as snail telephony.

The impetus for making the shift to DVD now is movies - replacing videotape. A DVD can be stamped out for less than a dollar, half the price of a videotape. The DVD is already available in stores as a videodisk, and will soon be used extensively with computers.

Microsoft plans to release Windows98 on June 25th, 1998. Windows98 will fully support the DVD (to the extent that DVD standards have been completed). In addition, Microsoft Windows NT 5.0, which is planned for release in the fourth quarter of 1998, will also support DVD. Macs and Unix will probably support DVD, but the effort is formidable and the speed and completeness of implementation are difficult to predict. Although the Microsoft releases may be delayed, it is very likely that DVD support will be included in the final versions. This is a significant milestone for the acceptance of DVD as a popular storage medium.

Storage Capacity

DVD readers and writers work exactly the same way that CD readers

and writers work. For computers, the DVD is a transparent replacement

for the CD-ROM, with the added benefit of a much larger storage

capacity - ten to thirty times larger than CD-ROMs (see Table 1). The

DVD comes in three versions:

DVDs come in two sizes: the mini-CD size of about 3 1/2 inches in diameter, and the standard CD size of just over 4 inches in diameter. This article only describes the standard-size DVDs. These DVDs look just like standard CDs, and have two usable sides. Each side can have two layers for a total of four layers per disc. Currently, there are no DVD drives that have two heads, so DVDs that have information recorded on two sides must be turned over. Two-headed DVD drives are technically possible, and will ultimately eliminate the need for disc flipping.

|

DVD ROM (Read Only Memory) |

(maximum of two layers per side) |

|

Top Layer |

4.7 Gb |

|

Bottom Layer |

3.7 Gb |

|

Single sided (two layers) |

8.5 Gb |

|

Double sided (two layers per side) |

17 Gb |

|

DVD WORM (Write Once, Read Many) |

(maximum of one layer per side) |

|

Single sided (one layer) |

3.8 Gb (lowest capacity of competing standards) |

|

Double sided (one layer per side) |

7.6 Gb |

|

DVD RW (Read Write, Rewriteable) |

(maximum of one layer per side) |

|

Single sided (one layer) |

2.6 Gb (lowest capacity of competing standards) |

|

Double sided (one layer per side) |

5.2 Gb |

DVD capacities stated in terms of number of documents, such as the number of books, boxes, sheets, and microfilm rolls that can be stored on a DVD, have been estimated by Archive Builders.

DVD and Multimedia

More important than the physical media, the DVD audio and video

file formats will establish the standards for digital representation

of audio and video recording. DVDs will force all PCs and PC networks

to support theater quality video and audio as described in Microsoft's

PC97, PC98, and PC99 specifications for PC hardware. With

the DVD, video and audio documents will be fully supported in digital

form. PCs with DVDs will become TVs with VCR functions, and TVs with

VCR functions will become PCs with DVDs. This will greatly expand the

reach of computing and digital libraries. Because so much material

will be produced in the DVD file formats, there should be many

conversion routines to migrate the material to newer formats that

will be developed in the following decades.

All of the file formats stored on DVDs are independent of the DVD media format itself. For this reason, anything stored on a DVD can be transferred to a magnetic disc or sent over the Internet. Copyrighted materials may have a digital lock built into the DVD format that inhibits this copying from the DVD.

DVD and High Definition Television (HDTV)

In support of HDTV, the United States Federal Communications

Commission has mandated that DTV (Digital TV) signals replace analog

signals for public TV by the year 2003. Again, additions to the DVD's

family of video standards are planned to force the PC platform to

accommodate another leap in performance, to theater quality HDTV.

(There is even an Ultra Definition TV standard, UDTV, waiting in the

wings.) The DVD will support HDTV through 2X (double speed) and

faster data transfers (paralleling CD speed increases). This higher

speed playback will provide theater quality HDTV, but will have a

shorter playing time than the current DVD video standard. To increase

the playing time, DVDs and DVD players will move to blue lasers,

providing 40 Gb of storage on a DVD ROM. As currently planned, this

"blue light special" will be backwardly compatible to existing DVDs

and CDs.

DVD Audio and Video Format Advances

In additional to being technological tours de force, DVD audio and

video formats are very international in design. With the DVD format,

a movie released on DVD can be played in eight languages with

subtitles for 32 more languages. The following DVD features will

probably become the de facto features for digital libraries:

Costs

In today's computer market, DVD readers cost twice as much as CD

readers, and DVD writers and media might cost up to twenty times as

much as CD writers and media. Even at these prices, some commercial

document management installations (such as

First Data Merchant Services)

has started switching to DVDs. The DVD writers and media costs are

expected to drop considerably in the third quarter of 1998 when the

first supplier begins to get more competition. It is predicted that

the DVD and CD costs should be about the same for media, readers, and

writers in about two to three years.

DVDs will provide an excellent medium for off-site backup. Storing duplicate digital library backups at more than one site (spatial diversity) minimizes risk at a relatively insignificant cost. What is destroyed at one site can easily be recovered from any one of multiple other sites. DVDs are also very inexpensive to store because they take up so little room.

Backward Compatibility

DVD readers can read CD ROMs. This means that DVD readers are

backward compatible for music and software CDs. However, DVD readers

can read some, but not all CD WORM. To avoid incompatibilities in the

document management environment, it is best to plan to convert all CD

WORMs to DVD WORMs before the last CD reader is decommissioned at a

given document management site.

Conclusion

DVDs make many previously infeasible applications feasible.

Digitizing all stored videos is an example. Digitizing large

collections of high resolution color images is another. However, for

many applications, CDs are already so inexpensive that the increased

efficiency of DVDs may not be a sufficient incentive for converting

to DVDs. The switch to DVD will come when the world moves to DVDs -

the same way 3½ inch floppies superseded 5¼ inch and 8 inch

ones. Today, many of us do not even have a computer that has a drive

for larger floppy disks. The pressure to convert to a new medium

occurs when it becomes too expensive to use something that no one

else uses.

DVDs will ultimately take over and replace CDs. With the two technologies converging in terms of price, and with DVDs handling many more types of material, this author predicts that the DVD will displace the CD rather rapidly. While the CD took 15 years to get to its present level of acceptance, the DVD may complete the cycle in the next year or two.

Fractal and Wavelet Compression

Steven Puglia, National Archives and Records

Administration

steven.puglia@arch2.nara.gov

As institutional interest in digitizing collections of oversized materials (maps, architectural plans, engineering drawings, etc.) increases, two methods of image compression, wavelet and fractal, have garnered a lot of interest. Both wavelet and fractal compression, along with the FlashPix file format (see Kevin Donovan's article in the April 15, 1998 issue of RLG DigiNews ), offer real advantages for providing access via the Internet to digital images of oversized materials. Currently, the National Digital Library project of the Library of Congress is using wavelet compression for accessing images of maps from the Geography and Maps Division. The images are compressed using software from LizardTech called Multi-Resolution Seamless Image Database (MrSID). The files are compressed to a ratio of 22:1 with minimal loss of image quality, and MrSID allows users to view segments of a map at different zoom levels and different tile sizes without having to load the entire high resolution image. Also, the Library of Virginia has used MrSID to provide on-line access to maps from the Virginia Board of Public Works (see Announcements). In the very near future, Aware Inc. is planning to release a competitive software package, based on their AccuPress wavelet compression software, that has similar and comparable features to MrSID. Live Picture's Image Server software, which utilizes FlashPix format files, also functions very much like MrSID. The tiles that are delivered via the Internet are JPEG format files derived on-the-fly from the FlashPix files. So there are several competing software packages that will provide more efficient access to large image files and will help to minimize on-line storage requirements through more efficient compression.

Unlike JPEG compression or LZW compression (used for GIF images) that maintain images as arrays of pixels, wavelet and fractal compressions convert images into mathematical models in order to save storage space. The math that underlies both wavelet and fractal compression is extremely complex, and of great interest to mathematicians, as can be seen by the numerous academic Web sites dedicated to its discussion. Like JPEG, both of these compression methods are "lossy," meaning some information in the original image file is lost during the compression process and can not be recreated during decompression. Generally, lossy compression (and compression in general) is not recommended for high resolution master files, but certainly can be used for access versions to facilitate downloading images via the Internet or a local area network, or to save storage space on file servers. Some applications use a combination of both wavelet and fractal compression. Iterated Systems has announced STiNG Technology, which combines both wavelet and fractal compression with lossless encoding. It is expected that Altamira Group will implement this technology in an updated version of their Photoshop plug-in, the update to be called Genuine Fractals Pro.

Wavelet Compression

Wavelet compression is a method of mathematical modeling of

images, which breaks the image down into small waves that represent

the frequency analysis of a function. The shapes and patterns in an

image are identified, and then described using mathematical functions

or formulas. The function that models or describes the image is

contained within the compression and decompression software. The

image file contains only the coefficients or numbers used by the

function, and compression is achieved by averaging the values of

these coefficients so that an image is represented by fewer numbers.

Wavelet compression is very efficient, with ratios up to 150:1. The efficiency of the compression and the quality of the image are very dependent on the images being compressed; typical wavelet compression ratios range between 15:1 and 100:1. As a comparison, typical compression ratios for JPEG are usually between 10:1 and 20:1 and for LZW around 2:1. Wavelet compression can take a longer time to compress images due to the complex math involved. However, the time required to decompress a wavelet or fractally-encoded image is usually comparable to decompressing a JPEG image.

An advantage of wavelet compression is that image processing can be incorporated into the wavelet transformation, including sharpening, contrast enhancement, and noise reduction for images. Also, images can be enlarged or reduced via embedded interpolation, using common interpolation algorithms, such as bicubic, bilinear, or nearest neighbor, as found in Adobe Photoshop and in other pixel-based image editing software. Generally the quality of this type of interpolation will not be as good as fractal interpolation. Both MrSID from LizardTech and AccuPress from Aware Inc. utilize wavelet compression with this type of image interpolation.

In addition to the map examples noted at the beginning of the article, wavelet compression is used in many varied digital applications: photographic images, audio and video recordings, 2D and 3D rendering, multimedia, fingerprints imaging (used by the FBI), medical imaging (radiography, MRI, etc.), satellite and remote sensing imaging, geographic information systems (GIS), and document imaging.

Fractal Compression

Mathematically, a fractal describes a structure that has many

repeated forms regardless of scale. Real world images have properties

that allow them to be described using fractals, such as repeated

shapes and patterns. Fractal compression works by using a variety of

methods to identify features within an image and then breaking down

the image into a mathematically modeled series of repeating shapes

and patterns. Fractal compression is very efficient, achieving

compression ratios of up to 250:1; typical fractal compression ratios

will range between 20:1 and 100:1. Images can be magnified or

reduced, because the compression process allows the modeled images to

be resolution-independent. When a fractally-encoded image is

converted to a pixel image, it can be enlarged or reduced to any

desired size with minimal loss of image quality. However, published

reviews of fractal compression software indicate that there is

probably a practical limit to how much a fractally-encoded image can

be enlarged before there is a significant loss of image quality;

perhaps up to 300% of the original size. Fractal compression can not

recreate detail that is not rendered in the original image file. In

order to render fine detail in the compressed image, you need to

start with a high resolution image that has captured that level of

detail.

Fractal compression can take a very long time to compress images - significantly longer than wavelet compression in test trials, but the decompression is relatively quick. One of the available fractal compression software packages, Genuine Fractals, is limited to working with color images and can not be used to compress grayscale images (the Genuine Fractals Pro upgrade should include grayscale compression capability). Fractal compression has been used in digital imaging applications for photographic images and video, although I was unable to locate any cultural institutions that are using fractal compression for current image projects.

Comparison

Both wavelet and fractal compressions have significant advantages and

disadvantages compared to JPEG compression, as the accompanying chart

illustrates. JPEG compression can represent a serious compromise

between image quality and file size; the more an image is compressed,

the greater the loss of image quality. Wavelet and fractal

compression have the advantage that image files can be more highly

compressed with less loss of image quality. Generally, for comparable

image quality, wavelet and fractal compressed files will be between

one-third to one-half the size of the same image compressed with

JPEG. Also, the perceived loss of image quality with wavelet and

fractal compression is often described as a softening of the image,

and usually viewers will prefer a soft image compared to the

blockiness and artifacts produced by JPEG compression.

The main disadvantage of both wavelet and fractal compression is that these compression methods are non-standard and almost always proprietary. There are many different implementations of wavelet and fractal compression algorithms, while the method of JPEG compression is standardized, and generally these days JPEG files are pretty much compatible between different applications. Also, using wavelet and fractal compression will require a dedicated viewer or plug-in for Internet access. Most software companies that offer wavelet and fractal compression provide free plug-ins for Web browsers; also, many of these plug-ins are available for different operating systems (Windows, Macintosh, and Unix) for cross-platform use of the images.

* Times measured on a 23MB RGB image scanned from a 35mm slide. All files were compressed using Adobe Photoshop 4.0 running on an Apple Power Macintosh 9500 with 244Mhz G3 upgrade. JPEG compression (at 60:1) was native Photoshop JPEG. Wavelet compression plug-in used was AccuPress from Aware Inc. (image compressed at 120:1). Fractal compression plug-in used was Genuine Fractals from Altamira Group, Inc. (image compressed 120:1).

JPEG

Wavelet

Fractal

Typical compression

10:1 to 20:1

15:1 to 100:1

20:1 to 100:1

Compression time*

8 seconds

45 seconds

13 minutes

Decompression time*

6 seconds

20 seconds

10 seconds

Image quality

excellent to poor

excellent to poor

excellent to poor

Resolution features

none

interpolation

scalable

Zoom

no in general;

yes with FlashPixyes

yes

Dedicated browser or plug-in required

no

yes

yes

Figure 1: Comparison of Compression Types on Image Quality (1:1 view)

Uncompressed

JPEG (60:1 compression)

Fractal (120:1 compression)

Wavelet (120:1 compression)

Figure 2: Comparison of Compression Types on Image Quality (1:3 - detail view)

Uncompressed

JPEG (60:1 compression)

Fractal (120:1 compressoin)

Wavelet (120:1 compression)

Conclusion

In conclusion, wavelet and fractal compressions offer the advantages

of higher compression ratios, comparable to higher levels of image

quality for the compressed files, and similar decompression times

compared to JPEG or LZW compression. Fractal compression has the

advantage of being resolution-independent, which allows end-users to

open a file at any desired resolution or size (only up to a point).

Wavelet compression can incorporate traditional interpolation methods

to enlarge or reduce images on-the-fly and, therefore, can function

very similarly to fractally-encoded images. The disadvantages for

both wavelet and fractal compression include long compression times,

non-standardized and proprietary compression algorithms, and the need

for a dedicated viewer or plug-in to use the files.

Iterated Systems' STiNG

technology offers the advantages of both types of compression

combined with lossless encoding, all of which should provide high

compression ratios, good image quality, and scalability. I suspect

that the advantages of both wavelet and fractal compression will end

up outweighing the disadvantages. We should soon see increased use of

both of these compression methods, along with increased use of the

FlashPix format, for delivering and viewing access images via the

Web.

Reference Articles

"Genuine Fractals: Plug-in Delivers Pixel-Free Format" by Deke

McClelland, MacWorld, February 1998.

"Transmitting Digital Files: Fundamentals of Image Compression" by Jack Drafahl and Sue Drafahl, Photo Lab Management, February 1998.

"Doing the Wave: Compression Engine Bests JPEG" by Jeff Sauer and Robin Marlowe, NewMedia, November 1997.

"Walking, Talking Web: Fractals and Wavelets, and Internet Savvy, Help Make Multimedia More Practical for the Net." by Edmund DeJesus, BYTE, January 1997.

"Wavelet Analysis: Revolutionary Tool for Data Analysis and Signal Processing." by Meredith Hoffman, SciTech Journal, Sept./Oct. 1996.

"Expert Column: Storing Images as Mathematical Constructs Instead of Bitmaps Saves Tremendous Space." by James Maisel, Personal Engineering, February 1995.

Also, most of the other vendors listed below provide general technical information about wavelet and fractal compression.

Wavelet and Fractal Compression Software

Aware Inc.

http://www.aware.com

Compression Engines

http://www.cengines.com

Infinop

http://www.infinop.com

LizardTech

http://www.lizardtech.com

LuRaTech

http://www.luratech.com

Summus Ltd.

http://www.summus.com

Iterated Systems

http://www.iterated.com

Altamira Group

http://www.altamira-group.com

|

Highlighted Web Sites ANSI

Online: Catalogs and Standards Information National Standards

Systems Network (NSSN) Custom

Standards Services (CSS) |

Calendar of Events

IEEE

Workshop on Content-Based Access of Image and Video Libraries in

Conjunction with CVPR (Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition )

'98

June 21, 1998

The objective of this workshop is to promote information exchange

and technical interaction among researchers and developers working on

algorithms or systems for accessing visual content in large

image/video libraries. This workshop will focus on several important

technical challenges, including representation, analysis, indexing,

retrieval, classification, and summarization of image/video content.

Digital

Archive Directions (DADs) Workshop

June 22 - 26, 1998

The focus of this two-part workshop is on issues of archiving

information in digital form. The primary goal of this workshop is to

discover on-going or existing work, conventions, best-practices, or

standards that have the potential for addressing digital archive

needs for a wide variety of communities. The first section is open to

the public; the second is restricted to individuals who have

submitted position papers.

Association of College and Research Libraries Program on

Digitizing at the American Libraries Association Annual Conference,

Washington, D.C.

June 29, 1998

The ACRL Western European Specialists Section, Arts Section,

presents a program entitled, "Digitizing a Continent: National-Level

Planning for Western European Libraries." This program will examine

the social, economic, and educational implications of information

digitization in Europe. The speakers will discuss digitization

planning in France and Germany, as well as a current implementation

at the University of Amsterdam. The program will be take place Monday

June 29, 1998, from 9:30-11:30 a.m. at the Lowe's L'Enfant Plaza

Hotel in Grand Ballroom A, B. For further information contact: Eva

Sartori,

evas@unllib.unl.edu.

TEI

and XML in Digital Libraries

June 30 - July 1, 1998

The goal of this meeting is to explore common problems and common

solutions for applications of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) in

large-scale conversion and encoding efforts, primarily in libraries,

and to explore the impact of Extensible Markup Language (XML), and

XML-conformant TEI on digital library efforts. The meeting is

sponsored by the Digital Library Federation and will be held at the

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. For more information and to

register contact: tei-

dlf@umich.edu.

Books at

Virginia: Rare Book School 1998

July 13 - August 7, 1998

Included in this year's program is a session entitled

"Introduction to Electronic Texts and Images," which will explore the

research, preservation, editing, and pedagogical uses of electronic

texts and images in the humanities. The course will center on the

creation of a set of archival-quality etexts and digital images, and

students will also create an Encoded Archival Description guide. The

instructor is David Seaman, who is the director of the

Electronic Text Center.

For further information contact:

biblio@virginia.edu.

Convergence

in the Digital Age: Challenges for Libraries, Museums and

Archives

August 13 - 14, 1998

To be held in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, this seminar is

supported in part by the European Union. The seminar is an

opportunity for those interested in the fields of libraries, museums,

or archives to share their experience of handling digital information

and to discuss common issues and challenges. The seminar is organized

around six main sessions, organization of knowledge in a digital

environment, citizen's access to digital heritage, new services in

their legal context, the future of the digital present, converging

technologies and standards for digital collections, and strategic

issues in research and technological development. For further

information contact: Johan van de Walle,

vandewalle@stb.tno.nl or

jvdwalle@bart.nl.

Preserving Photographs in a Digital World

August 15 - 20, 1998

Held at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, this

week long program focuses on traditional photo collection

preservation techniques and the digital imaging of photographs. The

basics of digital imaging will be explored and various image capture,

storage, display, and output strategies compared. For further

information contact: James Reilly,

jmrpph@rit.edu.

Creating

Electronic Texts and Images; Second Summer Institute at the

University of New Brunswick

August 16 - 21, 1998

The course is designed for librarians and archivists who are

planning to develop electronic text and imaging projects; for

scholars who are creating electronic texts as part of their teaching

and research; and for publishers who are looking to move publications

to the Web. Participants will learn to create electronic texts and

digital images. Topics to be covered include SGML tagging and

conversion, using the Text Encoding Initiative Guidelines, the basics

of archival imaging, the form and implications of XML, publishing

SGML on the World Wide Web, and EAD - Encoded Archival Descriptions.

Knowledge Creation - Knowledge Preservation - Knowledge

Sharing

The Museum Computer Network Annual Conference

September 23-26, 1998

The annual Museum Computer Network Conference is dedicated to

learning opportunities and information exchanges on all aspects of

technology use in museums. MCN '98 will explore the current issues of

creating, sharing, and preserving cultural knowledge. In addition to

practical pre-conference workshops, MCN will include presentations

from international speakers, drawn from within as well as outside the

community of museum technology professionals. The conference will be

held at the Loews Santa Monica Beach Hotel, in Santa Monica,

California. For further information, contact: Leslie Johnston, MCN

'98 Program Chair at (650) 725-5383 or

lesliej@leland.stanford.edu.

International Joint Workshop on Digital Libraries

September 7-9, 1998

An International Joint Workshop on Digital Libraries will be held

at the Asian Institute of Technology in Bangkok, Thailand. The three

days will include a two-day School on Digital Libraries, with

tutorials on networks, metadata, XML, and management issues for the

benefit of librarians and information providers in Southeast Asia.

For further information, contact: Thomas Baker,

thomas.baker@cs.ait.ac.th.

Announcements

Museum

Educational Site Licensing Project Reports Available

The following two volumes about the Museum Educational Site

Licensing Project will be available at the end of June from the Getty

Trust Publications. The titles are:

Delivering Digital Images: Cultural Heritage Resources for

Education

Christie Stephenson and Patricia McClung, editors.

This final report on the two-year project explores the legal,

technical, and practical issues involved in using digital images of

museum collections for educational purposes.

Images On-Line: Perspectives on the Museum Educational Site

Licensing Project

Patricia McClung and Christie Stephenson, editors.

This companion volume includes nine essays by project participants,

highlighting their experiences and recommendations. It covers the

impact of digital image availability on teaching, on university and

museum infrastructures, and also speculates about future legal

implications.

The publications can be ordered from Getty Trust Publications, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500, Los Angeles, CA 90049. Phone: (310) 440-7365

The UK Arts & Humanities Data

Service: Standards & Preservation Resource Lists

Two resources have been announced by the British Arts and

Humanities Data Service (AHDS). The first,

Standards for the

Interchange of Digital Information is a presentation of

organizations that are working on relevant standards for the

interchange of cultural resource material. The second resource

Digital

Preservation is a revised set of references to resources and

initiatives on the preservation of digital resources. In addition, a

paper entitled

Digital Collections:

Strategic Policy Framework for Creating and Preserving Digital

Resources is now available. The study is part of a program funded

by the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) of the Higher

Education sector in the UK, following a workshop on the Long-term

Preservation of Electronic Materials held at Warwick in November

1995.

The CEDARS

Project - The Consortium of University Research Libraries

(CURL):

The CEDARS project will provide guidance for libraries in best

practices for digital preservation. Cedars will be based on work

conducted at three lead sites (Oxford, Leeds, and Cambridge). CEDARS

is a three-year project funded by the Joint Information Systems

Committee (JISC) through the Electronic Libraries Programme (eLib).

For further information contact: Kelly Russell,

k.l.russell@leeds.ac.uk.

The New York Public Library

Launches Digital Library Collections

The New York Public Library has announced its Digital Library

Collections Web site, featuring a wide range of primary source

materials from The Library's four research libraries. Collections

include: the Digital Schomburg, comprising 56 texts and more than 500

images representing African American history and culture; Small Town

America: Stereoscopic Views from the Robert Dennis Collection,

1850-1910; The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

Millennium Project; Urban Landscape Photography in the Romana Javitz

Collection; and Berenice Abbott's Changing New York. For more

information about NYPL's Digital Library Collections contact: Pamela

Ellis, pellis@nypl.org.

The Library of Virginia

Digitized Map Collection

The Library of Virginia (Richmond) has released more than 750

digitized map images from its Virginia Board of Public Works

collection. The records of the Board of Public Works (1816-1903)

represent a unique source of information on social history,

economics, commerce, and engineering in Virginia. Using the MrSid

Image Retrieval software from

LizardTech which reduces very

large map images to "thumbnail" images embedded in the text of the

online inventory, the user can enlarge the map several times by

clicking on a portion of the image.

The Preservation

Map of Europe

The European Commission on Preservation and Access (ECPA)

presents "The Preservation Map of Europe" a virtual directory of

organizations working in the preservation field within Europe. This

map includes detailed information about preservation practice in

European countries and can be found at EPIC, the Internet site of the

ECPA.

Harvard

University Art Museums WWW Site

Visitors to the Harvard University Art Museums Web site can now

see how digital imaging techniques and technical examinations are

used to study paintings. The site addresses a variety of material

aspects of three Early Netherlandish paintings using digital imaging

technology. Visitors can examine and compare the artists' painting

techniques by viewing details of each painting.

The

Library of Congress/Ameritech 1997/98 and

The

National Endowment for the Humanities Division of Preservation and

Access

Award Winners Announced

Recently funded projects for digital imaging have been announced.

These projects range from digital education to imaging of significant

collections.

FAQs

Question:

In the literature for the scanner I am considering buying, two

different maximum resolutions are given: optical resolution and

interpolated resolution. What is the difference between these two

resolutions?

Answer:

Optical resolution, or "true resolution," indicates the actual

capturing capability of a scanner based on the size and placement of

its imaging sensors (in most scanners knows as the CCD array). The

sensing elements in a linear CCD array for a 600 dpi scanner are

spaced 1/600 of an inch apart horizontally, representing an optical

resolution of 600 dpi.

Interpolated resolution, also known as software-enhanced resolution, is achieved through software enhancements to the optical resolution. For example, if your scanner's optical resolution is 400 dpi, and its interpolated resolution is 600 dpi; you may increase your resolution up to 600 dpi through software enhancement. Interpolated resolution is attained by using software-based algorithms to calculate intermediate pixels occurring between two known pixels. Fulton's A Few Scanning Tips includes a section (Basics Part 7) on interpolated resolution, with a technical description of the interpolation process, and provides sample images to illustrate the difference between these two modes of resolution.

It is important to note that interpolation does not increase a scanner's ability to resolve small details, it only improves the perceived resolution. Interpolated resolution is commonly presented in marketing scanners to give the false impression that the scanner is capable of achieving a higher resolution than its actual capability. However, interpolated resolution is quite useful in certain processes, such as scanning text or simple line art documents. The interpolation helps to produce smoother lines, decreasing aliasing (jaggies) common in edges of bitonal scans.

As explained at the Microtech's Resolution and Scanning Web site, interpolation is also effective in enlarging (scaling) small documents. For example, if you need to scan and enlarge a 2" x 3" letter at 300 dpi using a scanner that has maximum 300 dpi optical resolution, you can interpolate the resolution to 600 dpi to enlarge the image to two times the original size. This process will create a 4" x 6" image while retaining clarity and sharpness. Although scaling can also be achieved after scanning by using image editing software, the outcome may be more satisfactory through interpolation.

Interpolation is also instrumental in matching a scanner's sampling rate (dpi) to a certain printer's resolution. For example, if your scanner's optical resolution is 400 dpi, and your printer's is 600 dpi, you can print your image at an interpolated resolution of 600 dpi to match the printer's resolution. This method is recommended for bitonal line art documents only.

Image quality is dependent on the effectiveness of the interpolation algorithm used and the document type. Therefore, if not used for the appropriate category of documents, or with an inefficient interpolation algorithm, interpolation can actually degrade sharpness and contrast due to the way pixel values are averaged. For example, it is recommended to avoid interpolation during color or grayscale scanning, as color averaging does not always produce satisfactory results.

We suggest that you examine scanning manufacturers' literature carefully to identify the optical resolution of the scanner you are considering purchasing or using. Some scanner specifications are presented in such a convoluted way that it is tricky to determine a scanner's true optical resolution. Ihrig and Ihrig suggest that if a scanner manufacturer advertises a horizontal resolution that is lower than the vertical resolution (e.g., 600 x 1400), you should assume that the lower one of the two numbers represents the maximum optical resolution. (1) The horizontal value, which is 600 in the above example, represents the actual number of sensor elements in the linear CCD array. Although it is advantageous to have interpolation capability associated with the scanner you are using, it should not be interpreted as a replacement for the true dpi that is represented by optical resolution. And as noted by Don Williams in an earlier RLG DigiNews article (2), a scanner's dpi is not the best indicator of its resolving power. Resolution should be assessed through sampling, and the utilization of MTF analysis tools.

(1) Ihrig, Sybil; Ihrig, Emil. Scanning the Professional Way. Berkeley, CA: McGraw Hill, 1995, p. 94. (Return to Text)

(2) Williams, Don. "What is an MTF ... and Why Should You Care?" RLG DigiNews, vol. 2, no. 1 (February 15, 1998), http://www.rlg.org/preserv/diginews/diginews21.html. (Return to Text)

RLG News

New RLG Tools for Digital Imaging

RLG has recently made available a new suite of tools designed to assist institutions with digital imaging projects. The tools were developed over the last year by Cornell University, under contract to RLG.

The need for these digital imaging "tools" had been expressed by RLG PRESERV member institutions and their development was identified as a priority in the current RLG PRESERV Strategic Plan. Specific needs identified included the development of a "model" Request for Information (RFI), a Request for Proposals (RFP), and a contract for digital imaging services - all similar in nature to those created for contract microfilming services and published in the two RLG microfilming manuals. Recognizing Cornell's experience with a variety of digital imaging projects, RLG contracted with them to produce the necessary tools. From this, the following documents were created:

The documents work in conjunction with one another to form a suite of tools that will enable institutions to plan, budget, and prepare for digital imaging projects. We encourage institutions to visit the PRESERV Web site and to take advantage of these new and exciting digital imaging tools.

Hotlinks Included in This Issue

Feature Article

Cornell

University, Department of Preservation and Conservation:

http://www.library.cornell.edu/preservation/pub.htm

RLG

DigiNews, December 15, 1997:

http://www.rlg.org/preserv/diginews/diginews3.html

Technical Features

Altamira Group:

http://www.altamira-group.com

Archive

Builders: http://www.ArchiveBuilders.com/aba003v10.html

Aware Inc.:

http://www.aware.com

Compression Engines

http://www.cengines.com

First Data Merchant Services:

http://www.firstdata.com

Iterated Systems:

http://www.iterated.com

Library of Congress,

Geography and Maps Division:

http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/gmdhtml

LizardTech:

http://www.lizardtech.com

LuRaTech

http://www.luratech.com

Microsoft's

PC97, PC98, and PC99 specifications:

http://www.Microsoft.com/HwDev/PC98.htm

RLG

DigiNews, April 15, 1998:

http://www.rlg.org/preserv/diginews/diginews22.html

Summus Ltd.

http://www.summus.com

Virginia Board of Public

Works: http://image.vtls.com/BPW

Highlighted Web Sites

ANSI Online:

Catalogs and Standards Information:

http://web.ansi.org/public/std_info.html

Custom Standards Services

(CSS): http://www.cssinfo.com/index.html

National Standards Systems Network

(NSSN): http://www.nssn.org/

Calendar of Events

Books at

Virginia: Rare Book School 1998:

http://poe.acc.virginia.edu/~oldbooks

Convergence

in the Digital Age: Challenges for Libraries, Museums and

Archives: http://www2.echo.lu/libraries/en/iflasem.html

Creating

Electronic Texts and Images; Second Summer Institute at the

University of New Brunswick:

http://ultratext.hil.unb.ca/Texts/Announce/seaman98.htm

Digital

Archive Directions (DADs) Workshop:

http://ssdoo.gsfc.nasa.gov/nost/isoas/us12/ws.html

Electronic Text Center:

http://etext.lib.virginia.edu

IEEE

Workshop on Content-Based Access of Image and Video Libraries in

Conjunction with CVPR (Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition )

'98: http://www.ctr.columbia.edu/cvpr98/workshop.html

TEI

and XML in Digital Libraries:

http://www.hti.umich.edu/misc/ssp/workshops/teidlf.html

Announcements

The CEDARS

Project - The Consortium of University Research Libraries (CURL):

http://www.curl.ac.uk/cedarsinfo.shtml

Digital Collections:

Strategic Policy Framework for Creating and Preserving Digital

Resources: http://ahds.ac.uk/manage/framework.htm

Digital

Preservation: http://ahds.ac.uk/resource/preserve.html

Harvard

University Art Museums WWW Site:

http://www.artmuseums.harvard.edu/Renaissance

The

Library of Congress/Ameritech 1997/98:

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/award/98award/award98.html

The Library of Virginia Digitized

Map Collection: http://image.vtls.com/BPW

LizardTech:

http://www.lizardtech.com

Museum

Educational Site Licensing Project Reports Available:

http://www.getty.edu/publications/index.html

The

National Endowment for the Humanities Division of Preservation and

Access: http://www.neh.fed.us/html/awards/preserv98.html

The New York Public Library

Launches Digital Library Collections: http://digital.nypl.org

The Preservation Map of

Europe: http://www.knaw.nl/ecpa/ecpatex/map

Standards for the

Interchange of Digital Information:

http://ahds.ac.uk/resource/standards.html

The UK Arts & Humanities Data

Service: Standards & Preservation Resource Lists:

http://ahds.ac.uk/

FAQs

A Few

Scanning Tips: http://www.cyberramp.net/~fulton/scans.html

Microtech's Resolution

and Scanning Web site: http://www.mteklab.com/res.html

RLG

DigiNews, February 15, 1998:

http://www.rlg.org/preserv/diginews/diginews21.html

RLG News

RLG PRESERV:

http://www.rlg.org/preserv/

RLG PRESERV

Strategic Plan: http://www.rlg.org/preserv/stratpres.html

RLG Microfilming

Manuals: http://www.rlg.org/pub.html#manuals

![]()

Publishing Information

RLG DigiNews (ISSN 1093-5371) is a newsletter conceived by the members of the Research Libraries Group's PRESERV community. Funded in part by the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR), it is available internationally via the RLG PRESERV Web site (http://www.rlg.org/preserv/). It will be published six times in 1998. Materials contained in RLG DigiNews are subject to copyright and other proprietary rights. Permission is hereby given for the material in RLG DigiNews to be used for research purposes or private study. RLG asks that you observe the following conditions: Please cite the individual author and RLG DigiNews (please cite URL of the article) when using the material; please contact Jennifer Hartzell at bl.jlh@rlg.org, RLG Corporate Communications, when citing RLG DigiNews.

Any use other than for research or private study of these materials requires prior written authorization from RLG, Inc. and/or the author of the article.

RLG DigiNews is produced for the Research Libraries Group, Inc. (RLG) by the staff of the Department of Preservation and Conservation, Cornell University Library. Co-Editors, Anne R. Kenney and Oya Y. Rieger; Production Editor, Barbara Berger; Associate Editor, Robin Dale (RLG); Technical Support, Allen Quirk.

All links in this issue were confirmed accurate as of June 10, 1998.

Please send your comments and questions to preservation@cornell.edu .

![]()