William Blake and the Emblem Tradition 1

Karl Josef Höltgen (Erlangen)

From Jesuit Emblems to Blake

It was J.B. Priestley who said that Blake was a "one-man religious revival". He was also a one-man revival of poetry, painting and the graphic arts, especially in the form of highly original symbolic word-image designs, his Illuminated Books. They appear to have some prima facie links with the emblem tradition.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE:

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Where is the bridge that takes us from the Renaissance emblem to William Blake working in London about 1800? In the eighteenth century, emblems were marginalized, but in the nineteenth century there was a real emblematic revival. Some years ago the present writer bought a rare book, Religious Emblems (London, 1809), with excellent wood engravings designed by the artist John Thurston and prose commentaries by the Rev. Joseph Thomas (Fig. 1). It is one of the best artistic achievements of the revival. There is ample evidence that the "William Blake, Esq.", who appears in the List of Subscribers, is the poet-painter. Religious Emblems is the only direct and personal link between Blake and an emblem book that has come to light (Fig. 2). It is modelled on the most popular and successful English emblem book, Francis Quarles's Emblemes, 1635, with nearly sixty editions up to the nineteenth century.2 Quarles established in Protestant England the Catholic emblems of the Amor divinus / Anima type. These books show the encounters of little Cupid figures representing Divine Love and the Soul. In these devotional emblem books, the tight structure of the earlier emblems is expanded by longer meditations. Two Jesuit works, Pia Desideria by Herman Hugo and Typus Mundi, served as models for the English poet.

Quarles was a middle-of-the-road Anglican Protestant and staunch supporter of The Church of England. The secret of his enduring success lies in the fact that he promoted (like his Jesuit sources) the general tenets of the Christian faith and avoided controversial theological doctrines or special cults. (Höltgen 1992, 1995). The Rev. Joseph Thomas selected over half the subjects of Religious Emblems from Quarles. He also wrote new interpretations for the wood engravings designed by Thurston and engraved by four other artists working under Thurston's direction. For a time Thurston enjoyed the highest reputation as a designer on wood. Religious Emblems became a much admired work.3 There was a second edition in 1810, and a German version entitled Sinnbilder der Christen. Erklärt von Arthur vom Nordstern was published in 1818 by F. A. Brockhaus in Leipzig (Fig. 3). The author hiding under that romantic pseudonym turns out to be Gottlob Adolph Ernst von Nostitz and Jänckendorf, a Saxon nobleman and civil servant with artistic and literary interests. He composed long and pious German verses to accompany the English plates.4

With regard to artistic technique, taste and sensibility Religious Emblems is highly original, innovative and modern. The new art of wood engraving achieves atmospheric lightness of touch and attention to detail and allows the pictorial expression of moods and emotions. The underlying aesthetics is that of the Sublime, of a pre-Romantic and Romantic spirituality. It is akin to the graveyard poetry of Blair, the Meditations of Hervey and the visionary experience of Fuseli (or Füssli) and Blake.

We will now compare examples from Quarles, Thurston-Thomas and some related images. Quarles, in an edition of Emblems Divine and Moral, 1808, no. I, 7 shows Amor humanus sleeping on a globe, unaware of the dangers of hell and death and unresponsive to the warnings of Divine Love (Fig. 4). Thurston-Thomas's emblem "Call to Vigilance", engraved by Clennell (Fig. 5), sets the allegorical scene in a cosmic space and transforms it into a dynamic encounter between light and darkness, angelic and diabolic powers competing for the soul of the pretty child who rests on the soft cushion of worldly comforts but will, let us hope, heed the Rev. Thomas's rousing call:

SLUMBERER, awake! see thy perilous situation. The foe is preparing his unerring shaft to strike thee down from thy couch of fancied security, into the dreadful gulph of perdition, that opens wide beneath to receive thee! Slumberer, awake! suffer not the syren Sin, with pleasure in her train, to lure thee through the broad and easy road that leads to destruction ...

Two versions of "The Soul Encaged" offer another example of the modern wood engraver responding to the old emblem picture reproduced in Fig. 6 with a concern for fine detail and iconographical and emotional sophistication (Fig. 7). He disregards the familiar emblematic device of adding a supporting subsidiary motif - here the small cage at the top with a released bird in the sky. Instead, he creates two new female personifications, the key-holders Birth and Death, imprisoner and deliverer, attendants at this prison of earthly life. They sit opposite each other; on the right, in full daylight, Birth, a young woman with her face averted, the crescent moon on her head signifying promises of growth and gifts whose uncertain realisation is hidden by the veil of time. On the left, all in darkness, the hooded but unmistakable figure and face of Death. In the middle, the pathetic figure of a well-dressed, beautiful young woman with long tresses clutches the bars of her elegant cage or prays for release. Both the English and the German commentator emphasize the original spiritual meaning clearly expressed in Quarles's motto from Psalm 142:7 for Emblem V, 10, "Bring my soule out of Prison that I may praise thy Name", and in his opening lines:

My Soule is like a Bird; my Flesh, the Cage;

Wherein, she weares her weary Pilgrimage ...

If Thurston's birdcage image should suggest additional social or feminist readings to a modern critic they ought not to be roundly dismissed considering the great number of relevant references to golden and other cages in Victorian art and literature. To quote some examples: Barry Qualls (1982, 89-81, 206) writes perceptively on the emblematic origin and secular transmutation of the birdcage image in Dickens, especially in Little Dorrit. Charlotte Brontë gives the emblem its traditional meaning, but Jane Eyre, freed from "the soul's cell", finds salvation in this world. Mrs. Gatty's emblem of the caged bird, "enslaved, yet not wishing to be free", signifies the heavy weight of custom (Gatty 1872, 12) (Fig. 8). The various constraints of Victorian womanhood are similarly represented by Tennyson (In Memoriam, st. 27) and Elizabeth Barrett Browning (Aurora Leigh, bk. I, 310). In a Pre-Raphaelite painting, The Awakening Conscience, William Holman Hunt captures the moment when the kept woman (in his words) "is breaking away from her gilded cage." A popular American Music Hall song of 1892 by Harry van Tilzer ends with the lines: "And her beauty was sold, / For an old man's gold, / She's a bird in a gilded cage." A.S. Byatt, in her acclaimed novel Possession (1991, 283), records her Victorian heroine Christabel LaMotte's experience of advancing from self-protection to sexual self-determination; at this point the narrator draws attention to an emblematic piece of female attire: "On one chair stood a kind of trembling collapsed cage, the crinoline, with its steel hoops and straps."

A drawing from the Notebook of William Blake (also known as the Rossetti Notebook) shows, according to its editor, David Erdman, a boy who huddles in a birdcage hanging from a bough while a bird hovers outside. The boy is clad and his hands cover his face.5 (Fig. 9) It is one of a number of sketches scattered throughout the Notebook called by Erdman "Emblems of Fear and Hope" from which were selected the engravings for The Gates of Paradise. These seventeen engravings, first issued in 1793 with a headnote "For Children", are also described as "emblems" by modern editors and critics. There may be some justification in applying the term to such a word/image composition consisting of picture and caption or motto (the "Keys to the Gates", which could be regarded as epigram, were added about twenty-five years later in a re-issue under the title "For the Sexes"). Critics should be aware that Blake himself never discussed the genre of the emblem, used the word only a few times and never with reference to an emblem book or its constituent parts.

With its small format, its distribution of the verbal and pictorial matter on the page, its didactic purpose and gradual unfolding of the theme of the successive stages of life, The Gates of Paradise is Blake's nearest approach to a conventional eighteenth-century emblem book as represented by John Huddleston Wynne's Choice Emblems (Fig. 10) and the later editions of Quarles. Blake had been working on the emblem sketches in the Notebook for some time. It is probably not accidental that he published some of them, after a laborious process of selection, as The Gates of Paradise in 1793: in or about that year a new edition of Quarles's Emblems and Hieroglyphics appeared, and the first of many editions of Wynne's Choice Emblems (also known as Riley's Emblems after their publisher) had come out the year before (Fig. 11). For his adaptation of a traditional genre Blake did not employ his innovative technique of relief etching but went back to line engraving. The format, the method of illustration and the didactic theme of the stages of life are customary and appropriate for an emblem book; but Blake's treatment is original and reflects his own spiritual views. The question of the frontispiece, "What is Man!", receives its answer through the picture of a caterpillar and a chrysalis. Man is both mortal worm and sleeping butterfly or soul. (Quarles, too, chose a chrysalis as emblem for "Infantia" in Hieroglyphikes of the Life of Man, no. 9, but in some later editions it has become unrecognizable.) Blake's emblem sequence in the Gates traces humanity's progress through the fallen world of vegetable and elemental existence, the division of the sexes and corruption of reason to the Gates of Paradise, i.e. the redemption of the soul and the return of the body to the worm. To describe this process in emblematic images: the youngish, fashionably dressed traveller hastens through "evening shades" towards the light of the sun but arrives, as an old man, at Death's Door and must step over its threshold to come to the Gates of Paradise. The serious moral purpose behind the symbolic pilgrimage is emphasized by the gnomic opening lines in the second edition "For the Sexes":

Mutual Forgiveness of each viceThe birdcage sketch in the Notebook (Emblem 7) was not selected for The Gates of Paradise. It is related to a contrary sketch (Emblem 50), in which the cagedoor is opened, the bird is gone and a naked boy flies like a bird - hints of progress from oppression to liberation. Details of cage and bird in the first sketch, also the boy's similarity to a Cupid, leave little doubt that it was inspired by Quarles's Emblems, one of several emblem books Blake would have encountered in his long career as professional engraver and printseller. Another one is Wynne's Choice Emblems (see edition 1742, nos. 24, 27).

Such are the Gates of Paradise.

Two other designs recall Blake's illustrations for Robert Blair's popular poem The Grave, published in 1808, just one year before Religious Emblems. (The publisher of both works was Thomas Bentley.) The two relevant plates from The Grave are the "Death of the Strong Wicked Man" and "The Death of the Good Old Man". Their counterparts in Religious Emblems are called "Hope Departing" and "The Joyful Retribution". Blake began working on the drawings in 1805. He suffered great distress when, against all expectation, Cromek, the publisher, entrusted the engraving not to him but to Schiavonetti. Blake's designs in the Gothic style for this "improving work" (as it was called) remained well known up to Victorian times although their visionary quality provoked violent attacks by some contemporary critics. The unifying concept of the twelve published illustrations is, in the words of the commentator, probably Cromek, "the regular progression of Man, from his first descent into the Vale of Death, to his last admission into Life eternal."6 In a German essay on Blake of 1811, Henry Crabb Robinson observed that the Grave designs marked the turning point in Blake's contemporary reputation: "In der That gelang bis jetzt erst ein Versuch ihn bey dem grössern britischen Publikum einzuführen, durch seine Zeichnungen zu Blair's Grab, einem bey ernsten Gemüthern sehr beliebten, religiösen Gedicht ..." ("up to now only one attempt at introducing him to the great British public has indeed succeeded, his illustrations to Blair's Grave, a religious poem very popular among the serious ...").7

Early in 2002 English and German newspapers reported the sensational rediscovery of nineteen watercolours painted by Blake in 1804. They represent his designs of illustrations for a new edition of Blair's popular poem The Grave, issued by the publisher Cromek in 1808. Cromek paid Blake a meagre fee and, much worse, gave the lucrative enrgaving commission not to him but to the more fashionable Schiavonetti. The watercolours are aid to doverge from the known engravings. Since Cromek's widow sold the watercolour designs in 1836 for oune pound and five shillings they have been lost and forgotten until now. One hopes for further results of the initial research carried out by a group of experts including the distinguished Blake scholar G.E. Bentley. The authenticity of the watercolours is not in doubt. Their present custodian, an art dealer in the West of England, thinks they will fetch more than one million pounds (1,64 million Euros) at an auction.

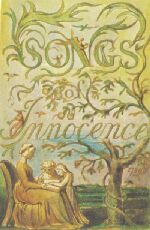

Blake's influence on Thurston's designs is not only suggested by the visible evidence of the two pictures but also by external circumstances. The Rev. Joseph Thomas of Epsom subscribed to the Blair volume containing Blake's designs. His subscription was one of the many acts of kindness, friendship, active interest and generous patronage he had extended to Blake for the last eight years. He first approached Blake in 1801 through Flaxman, called on him at Felpham and over the years formed a considerable collection of Blake's works.8 He was a real Blake enthusiast and Mrs Flaxman reports that he "wished to collect all B____ has done."9 He bought twenty-six water-colours, a copy of Songs of Innocence and Experience and two engraved volumes. Further details of his life and patronage will be found in a Note appended to this article. He married an heiress, the daughter of the Rev. John Parkhurst of Epsom near London, then fashionable and famous for its waters and the horse race. Thomas was able to devote much of his time and wealth to patronage and artistic pursuits.

Religious Emblems is Thomas's only publication. In view of the circumstances, the subscriber "William Blake, Esq." must be our Blake, although he was not usually so styled and there are several confusing namesakes. On the question of "Esq." it should be pointed out that in his Marriage Bond of 1782 engraver Blake, a mere artisan, declared himself "Gentleman", that all his life he entertained fantasies of higher status and that most of the artists in the List of Subscribers are styled "Esquire". An earlier subscription, probably by him, in a Proposal for Cowper's translation of Homer, 1791 (John Johnson Collection, Bodleian Library) has already "W. Blake, Esq." Cromek, Fuseli, Flaxman and Cosway subscribed to Religious Emblems, as did Thomas's many friends and relations, some art dealers and publishers, members of the nobility, and army officers associated with Edmund Boyle, eighth Earl of Cork and Orrery, a General in the army, Whig politician and the dedicatee of the book. Blake's subscription can be regarded as a token of gratitude to his patron and a sign of his interest in the new emblem book. On the other hand, Thurston and Thomas would have seen Blake's designs for The Grave because they were circulated and much discussed even before publication.10

Fig. 13

Fig. 14

And yet, this image of despair is but a tamed and domesticated version of Blake's "Death of the Strong Wicked Man" from Blair's Grave (Fig. 13). This man, too, has spurned the sacrament and broken the chalice. But, following Blair's text, the artist has created an embodiment of extreme strength laid low, dying with deep groans of pain and anguish. A critic in the Antijacobin Review of November, 1809 (Bentley 1969, 204-205), praised the portrayal of the body convulsed by agony, the expanding chest heaving with inexpressible pain, the swelling muscle, also the frantic sorrows of the despairing wife and the mute yet expressive woes of the afflicted daughter. Although Fuseli had commended Blake's invention, the Antijacobin critic was shocked at the outrage done to nature and probability by "a perfectly corporeal realisation of the masculine Soul" hurried through the casement in flames. Facial expression and body language of the Wicked Man and of his copy, the Soul, speak of extreme terror. David Bindman, the distinguished art historian and Blake scholar, thought my suggestion of Blake's influence on the Thurston-Thomas picture a very plausible one, and in a letter of 1975 he remarked: "Behind both I suspect there lies a remembrance of Fuseli's Nightmare" (Fig. 14).

In his book on Blake, Bindman confirms the point (1977, 147-148). He notes that the Strong Wicked Man and the Good Old Man represent two different manners of dying - resistance in terror and acceptance in serenity - and two different artistic modes: "The death of the Wicked Man is full of Sublime terror; his Michelangelesque body is contorted in pain, his head thrown back like the victim of the nightmare in Fuseli's painting which it resembles in other ways." The design of the Good Man recalls tomb effigies, perhaps even Blake's youthful studies of tombs in Westminster Abbey.

The importance of The Nightmare, Fuseli's most famous painting, cannot be overestimated.11 Painted and first exhibited in 1781 at the Royal Academy, its several oil and print versions prompted reactions of shock and fascination and numerous imitations and caricatures throughout Europe. A sleeping girl whose head and arms are hanging over the end of the bed is haunted by a misshapen, leering Caliban-like incubus squatting on the pit of her stomach. The head of the horse on which, according to folk superstition, the incubus travels, peers through the curtain hangings with wildly staring eyes. A bedside table carries a tray, jars and a dressing-mirror. In this picture the squatting incubus is the nightmare, not the horse. The word derives from Old Norse mara, an evil spirit, and the association with mare, a female horse, is a later development.

While Fuseli as an artist became a specialist for the phantoms of the unconscious or superstitious mind, for dreams, spirits, devils, witches, fairies and incubi, he was also a modern rationalist and critical thinker. His friendship with Blake, which began in 1787 and led to an intense exchange of ideas and mutual influence upon one another, suffered from his objections to Blake's mysticism. He tended to dress his spirits in modern, fashionable attire and place them in modern settings. It is said that the fashionable dressing-mirror in The Nightmare shows no reflection of the horse and the incubus: they are not part of empirical reality but figments of a troubled imagination. Fuseli knew about medical explanations of nightmares as (in Dr. Johnson's definition) "a morbid oppression in the night, resembling the pressure of weight upon the breast." In The Nightmare he fused private obsessions, classical and modern artistic traditions, folk tales, medical and psychological observations into a somewhat lurid, but powerful and disturbing image. It was probably inspired by his hopeless passion for Anna Landolt, a niece of Lavater's, whom he met in Zurich about 1779 and seriously wanted to marry. Her father refused him, and she married another man. In a letter Fuseli speaks of his dreams and sexual fantasies about her, and the portrait of a young woman on the back of the canvas may well be Anna's. Significantly, the sleeping girl in The Nightmare wears a heart-shaped pendant on her breast.12 For Fuseli, the squatting incubus may have symbolically taken the place of Anna's hated husband or of himself in his rage of jealousy and desire. Such circumstances, together with the telling details of the picture, leave little doubt that the sleeping girl is supposed to experience a violent sexual assault in her dream. The lifeless, prostrate body, dangling arms, flung back head and open mouth appear to be petrified by the impact of the horrible dream and the inability to move or cry caused by the suffocating and oppressive power of the nightmare. These pertinent motifs of Fuseli's painting reverberate through Blake's symbolic iconography and beyond, for instance in the figure of Oothoon whose defenceless female body is tortured by an eagle with blood on its wings symbolizing the brutality of war,13 or in the "Death of the Strong Wicked Man" in The Grave and the death of the atheist in Thurston and Thomas's "Hope Departing". The two impious men are facing nothing less than the instant terrors of hell. They are true "figures of despair".14

Fig. 16

Blake's deathbed scene of the Good Old Man is entirely peaceful and pious (Fig. 15). The hand of the man who has just died rests on the open "New Testament". Bread and wine, the elements of the Eucharist which he has received, can be seen on the bedside table. But Blake's picture is unashamedly visionary where the wood engraving is allegorical. It was Blake's avowed intention "to connect the visible and the invisible world without provoking probability."15 While the Antijacobin critic praised the humility and Christian resignation shown by the kneeling relatives, he strongly objected to the two winged angels who bear the soul of the departed towards heaven and should have been "veiled by the gossamer" rather than depicted "with all the fulness and rotundity of mortal flesh." (This refers to the one visible leg protruding from the feathered wing of the angel on the right). The critic seems obsessed with the dress code for spirits. He thinks it absurd to give the "same habiliments" to the spirit of the good man borne away by the angels and to the body on the bed. Incidentally, later versions of the Good and Wicked Man are still being published in popular Pietistic tracts in Germany and the United States (Fig. 16).16

Blake and the Emblem

It has been shown how Jesuit emblems of the Baroque age, adapted by Quarles and transmitted through his book to the early nineteenth century were absorbed into a revival movement of the graphic arts and contributed to a significant new emblem book by Thurston and Thomas that was also influenced by Blake. It is now necessary to examine Blake's attitude to the emblem in some detail. The subject is fascinating but elusive. Blake had such a strong visual memory that he would hardly forget anything he had seen in his reading or work as a student, apprentice and professional engraver and printdealer. Emblems, hieroglyphics, Hebrew and classical antiquities, medieval illuminated manuscripts, Renaissance prints, paintings and sculptures, plates and title-pages of alchemistic books or Cabbalistic and Neoplatonic cosmogonies, antiquarian and architectural illustrations, eighteenth-century educational and religious books and Masonic symbols17 - they were all grist to his mill and left their traces and transformations in his Illuminated Books. If there was preference or selection, it would have been in favour of texts and images which promised the rediscovery of ancient and occult spiritual knowledge. The emblem has only a limited share in these traditions.

The term "emblem" has become quite fashionable in recent Blake scholarship (a result, no doubt, of the upsurge of emblem studies), but is often used in the wide, unspecific sense of visual symbol or meaningful object. Peter Ackroyd (1995), for instance, in his excellent new Blake biography speaks of the London cityscape as an emblem of the mortal body, or of the Albion Mill in Lambeth as an emblem of industrialized England. What is meant here is not quite the same as the bimedial and (ideally) tripartite emblematic genre. However, especially the second example is an illuminating formulation which opens up avenues of Blakean iconography. It can lead us on to "these dark Satanic Mills" of the introductory hymn to Milton and to the "Satanic Wheels", illustrated by three sinister, black cogwheels (cf. Jerusalem, Plates 12 and 22). This image originates with Milton's Samson slaving eyeless at the mill of the Philistines and its ultimate meaning extends beyond the evils of industrialization to Satan's enslavement of the human mind.

Blake himself uses the words "emblem" and "emblematic" only five or six times (one phrase occuring in two places). Erdman's Concordance (1967) gives these references:

- "Rome, seated on seven hills, the mistress of the world, Emblem of Pride"; [She bore pale desire], ante 1777.

- the tender maggot, emblem of Immortality"; Four Zoas, Pl. 9.

- the same in Milton, Pl. 27.

- "Joseph, an infant ... wrap't in needle-work / Of emblematic texture"; Milton, Pl. 24.

- At Albion's death, the Divine Lord built "a sublime Ornament, a Couch of repose / With Sixteen pillars canopied with emblems & written verse, / Spiritual Verse ... order'd & measur'd from whence time shall reveal ... The Four-fold Gospel, and the Revelations everlasting"; Jerusalem, Pl. 48.

- When peace negotiations with Napoleon began in 1801, Blake wrote to his friend, the sculptor Flaxman about his hopes that England and France, their countries and arts, would be united and "that you will Ere long be erecting Monuments in Paris - Emblems of Peace"; Letters, ed. Keynes (1980, no. 36), 19 October 1801.

These samples do not suggest a specific theory of the emblem but rather a wide, inclusive concept of an essentially pre-Alciato provenance. It comprises the allegorical representation of a moral quality or vice through the female personification of a city (Rome in 1); the etymologically based notion of inlay or patchwork (Joseph's many-coloured coat in 4 with the possible meaning of fickleness); the forshadowing of spiritual truth by natural objects (maggots were thought to arise by spontaneous birth in dead flesh, 2 and 3); the architectural, monumental and decorative functions in 5 and 6 and - most important - the emblem as God's chosen device for the recording of hidden messages and promises, which will be fully revealed at the Second Coming when every division and corruption will be healed and reduced to order and beauty; the "Couch of repose" in 5 is the Bible consisting of the inspired books approved by Swedenborg, whom Blake admired for a long time as a "divine teacher" and who states in Arcana Coelestia that emblems correspond to sacred things. For Blake the most significant aspect and highest function of the emblem would be that of a sacred hieroglyph.

Attempts to identify specific emblematic sources for Blake's designs often remain inconclusive and only result in similarities and analogies. Well-established sources include the "hieroglyphic" illustrations of Bryant's Ancient Mythology (1774-76), a work on which Blake was employed as an apprentice, viz. the winged disk or ring and serpent (cf. the sunwings and bat-like spectre wings in Jerusalem, Pl. 33 and elsewhere), the mundane egg (cf. Gates of Paradise, Pl. 2), the moon-ark (cf. Jerusalem, Pl. 24, 39) and the chrysalis and butterfly (cf. Jerusalem, title-page and Pl. 14); furthermore, as mentioned before, Quarles's birdcage emblem V,10, adapted in the Notebook, and perhaps the preceding Quarles emblem of the Soul chained to a globe (V, 9), with a possible adaptation in Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Pl. 4; also from Wynne's Choice Emblems, no. 24, the fashionable traveller, bitten by a snake coiled around his right leg (a variation in Gates of Paradise, Pl. 14, and the telling detail of the coiled snake in Notebook, N 13a). A related figure of a young man trying to catch a butterfly in Wynne, no. 27 appears transformed in Notebook, Emblem 4 and in Gates, Pl. 7. The clipping of Cupid's wings by Chronos in Vaenius' Amorum Emblemata, 1608, p. 236, or similar scenes in other Renaissance emblem books and paintings may have been responsible for the design of Gates, Pl. 11.

Readers of Blake will recall that throughout his work one finds separate symbolical objects, attributes or signs, repeated and modified according to the continuously evolving functions of the protagonists: compasses (for the Ancient of Days, Urizen, Newton), hammers, anvils, tongs, chains, suns, moons, stars, clouds, trees, flowers, birds, serpents and "tail-eaters" (ouroboroi), trilithons, caves, ropes, nets, distaffs, buckets, even small models of a Grecian temple, a Renaissance dome and a Gothic cathedral. These emblem-like signs serve as a convenient shorthand to inscribe a maximum of meaning in the limited space of a symbolical design. They are not real emblems but perhaps incomplete emblems.18 Blake's treatment of the human body as a living, expressive and symbolic form has also been called emblematic.

A recent important study by Viscomi (1993), based on an analysis of about 168 surviving copies of Illuminated Books, sheds new light on the technical aspects. It opens the door to Blake's studio and the practice of his inspired cottage industry. He drew and painted words and images spontaneously, simultaneously, and directly on the copper plate using a varnish which would resist the corrosive power of aquafortis and produce a design in relief. This would then be inked, printed, and hand-coloured. He worked without preparatory drawings and often without previously drafted text. The text was written in reverse and no transfer was employed for text or image. The printing was done for a few concentrated weeks a few times a year and for a few years only.

Unity of concept and execution achieves unity of presentation, which does not preclude the aesthetic independence of poem and picture in this composite art.22 It is found in Blake's other Illuminated Books, too. The two arts often complement and interanimate each other, or they may part company for a time and follow their own thematic and formal connections with other compositions. (It has been observed that Blake developed a system of recurrent schematic forms associated with the senses.)

Fig. 20

Fig. 21

Bibliography

Bibliography

We will briefly return to "The Tyger" for one last comparison. Could one really imagine Blake's "The Tyger" turned into an emblem, perhaps with the motto "Fearful Symmetry", a suitable picture and a neat epigram? It seems that the awesome creator or demiurge and the terrible energy of the creative and destructive powers at work in the fiery furnace and forge of "The Tyger" cannot really be contained in a picture, only in the magical words of the poem. In a rejected design, originally intended for Experience, showing Los, the poet and craftsman identified with Blake himself, forging with his mighty hammer a human form out of the sun or globe on an anvil, Blake has compressed some aspects of the violent, creative action of the forge of "The Tyger" in a small emblem-like picture with short verses, entitled "A Divine Image"23 (Fig. 20). The plate was not published by Blake and printed posthumously. "A Divine Image" seems to have been intended as a contrary poem to "The Divine Image" from Innocence. It is a savage denunciation of the corrupted divine image in man. The important figure of Los in his creative furor appears in several other designs by Blake. "A Divine Image" is a minor piece but gives us, powerfully and unmistakably, Blake. As it happens an emblem by Sambucus, "Simul et semel", published in 1564, has iconographical similarities (Fig. 21). It portrays God the Father standing apart from hammer, anvil, tongs and some creatures, holding in his hands a heart and a liver. No visible action is going on.24 The motto may perhaps be translated as "At the same time and together". The epigram explains that God created all things at once and together (like the heart and the liver) without separation through time and space. The emblematist thinks that this consideration should help to relieve burning sorrows. Here I do not suggest another emblem source for Blake. On the contrary, I wish to contrast the Renaissance emblem as a didactic table demonstrating lessons of Humanist practical wisdom to Blake's compositions which are attempts to transform into word and image unbounded energies and opposing forces in life and art on the authority of his own personal vision. His mature artistic practice is neither naturalistic nor allegorical nor strictly emblematic; it may be called figurative in the sense of fashioning living and expressive symbolic forms, mainly those of the human body. In his aesthetic thought Blake unifies sublimity and imaginative beauty and affirms the centrality of the body as structural principle of space.25 The emblem tradition had a limited influence on Blake, but the emblematic genre can serve as a touchstone to show up the differentia specifica, the distinct quality, of his composite art.

Notes:

1 An earlier version of this essay, "Religious Emblems (1809) by John Thurston and Joseph Thomas and its Links with Francis Quarles and William Blake", appeared in Emblematica 10 (1996), 107-143. The copyright of the original version is still held by AMS Press. Our thanks go to Mr. Gabriel Hornstein, President of AMS Press, Inc., New York, for the permission to make use of K.J. Höltgen's work.

2 For Quarles, Emblemes (1635) and Hieroglyphikes (1638) see the edition by Höltgen and Horden (1993); also Höltgen (1978, 1986); Bath (1994); Daly and Silcox (1989).

3 On Religious Emblems see Höltgen (1978, 313-314); Bath (1993, 1994, 266-271); Paultre (1991, 177-180) and earlier comments by Chatto and Jackson (1861, 520).

4 For Nostitz (1765-1836), a prolific amateur poet and Konferenzminister of the Kingdom of Saxony, see Voigt (1929) and Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 24 (1887). Copies of Sinnbilder der Christen have been located in the Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg, shelfmark 02/ III.8.4.65, and the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, München, shelfmark SB 418/7, which also holds the second edition of the English original under SB 409/1. I gave a brief description of the German book in Newsletter of the Society for Emblem Studies 21 (1997), 7-10.

5 Erdman (1973, Emblem 7, pp. 17, 78 and N23, also Emblem 50, p. 27; 1975, 268-279.

6 Blake's Illustrations to the Grave, a reprint of the designs only (1973), London: Wildwood House.

7 "William Blake, Künstler, Dichter, und religiöser Schwärmer", from Vaterländisches Museum, 1811; repr. Bentley (1969, 433).

8 Flaxman to Blake, 31 July 1801; Letters of William Blake, ed. Keynes (1980, 33), third edition, Oxford University Press. Blake to Flaxman, 19 October 1801 (ibid., 38).

9 Nancy Flaxman to John Flaxman, September 1805, Bentley (1969, 165-166).

10 In the "Advertisement" of July, 1808 to his edition of Blair's Grave, the publisher Cromek states that he had submitted Blake's drawings to eleven members of the Royal Academy who acknowledged their excellence.

11 Powell (1973); Henry Fuseli 1741-1825 (1975), Exhibition Catalogue, London: Tate Gallery.

12 It is not visible in all versions of the picture but can be seen in the early Carrick-Moore drawing which, incidentally, omits the horse (Powell, Fig. 21).

13 Plate 13 of America A Prophecy; cf. the similar Plate 3 of Visions of the Daughters of Albion.

14 This iconographical type is also recognizable in a rough sketch for "Death of the Strong Wicked Man", c. 1805; Keynes (1970, no. 39) cf. Warner (1973, 208-224).

15 For this and the following quotations see Bentley (1969, 204-205).

16 These two images have been incorporated in the immensely popular series of emblems of the heart entitled Das Herz des Menschen by Johannes Gossner (1811 ff.). I know of editions Lahr, Baden (1977) and Baltic, Ohio (ca. 1950). Gossner (1773-1858), a Catholic priest and a Pietistbecame a Protestant in 1826 and was Pastor of the Lutheran Bohemian Bethlehem-Kirche, Berlin, from 1829 to 1846.

17 The Freemasons' Hall and Tavern were in Lincoln's Inn Fields just outside the workshop of James Basire, to whom Blake was apprenticed.

18 Foster Damon's Blake Dictionary (1965) may sometimes help to establish their meaning.

19 I think Blake was aware of the discrepancies, and this may be one of the reasons why he did not in fact call the book "Emblems of Fear and Hope" or "Emblems of Doubt and Vision".

20 See Raine (1968, 1977).

21 See, for example, "The Sick Rose", which could be regarded as an emblem. But the poem, in the words of Seamus Heaney (1980, 83), "drops petal after petal of suggestion without ever revealing its stripped core: it is an open invitation into its meaning rather than an assertion of it."

22 W.J.T. Mitchell (1978) advances further on the path opened up by Northrop Frye (1947) and Jean Hagstrum (1964).

23 Erdman (1975, 389).

24 Sambucus (1564, 135).

25 Baulch (1997, 345-348).