The Poet of Political Incorrectness:

|

|

| What would happen to all our life, without negative emotions? What would happen to what we call art, to the theatre, to drama, to most of the novels? (P.D. Ouspensky, The Psychology of Man's Possible Evolution, 1974) |

Any revolution will provoke outrage from one part of the population as it will fire the enthusiasm of the other. Premarital sexual intercourse an important divide but not the single issue of the generation conflict which accelerated the cultural revolution of the 1960s; this was the area of emotional experience and conflict for the mature Larkin. The purpose of this paper is to reshuffle a number of points raised by the Larkin industry, even if it may be coming too late. Larkin's favourite pattern of poetic self-fashioning was withdrawal, isolation and self-deprecation, but, unsurprisingly, he was at the centre of an old-boys network reaping a number of rewards and honours. Larkin was well present to the public mind, although, his public image and reputation changed when his hitherto unpublished views on politics and on contemporary society became widely known: Larkin, Jekyll and Hyde-like, the maniac and irresponsible and foul-mouthed Tory, Larkin not the post-war poet of Englishness and successor to Betjeman, but Larkin the notorious prophet of political incorrectness? Was this spiteful writer to prove equal to the rank of Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope in the congenial company of English literary history? It was Pope who had similarly attacked the vulgarity of the rising middle classes; some 250 years later, when the postwar world had created the new socio-economic climate of mass affluence and consumerism, when the middle classes dominated no longer English culture and when the age of a pleasure-and-sexuality-ridden and media-directed society was dawning, Larkin spread his venom in lines worthy of the pen of the Augustan satirists. Whatever judgment the reader will pass on Larkin's poetry of postwar society, as any tribute to Larkin may be considered an act of irresponsible sympathy, it would be untrue to play down the fact that the writer wearing his emotions on his sleeve and carrying them into his poetry must be aggressive in order to make the reader see and that his perception of social change will often be tainted by a pathological twist of mind. Some critics expressed their serious concern about Larkin's collision "between the aesthete and the philistine". 1 However, outrage expressed satirically has been a time-honoured and acknowledged strategy in English poetry. As a poet and an eye-witness to the revolution, Larkin released a torrent of basic human emotions. I would like to argue that critics have seriously underestimated the anger, fear and bewilderment people like Larkin felt on being haunted by general decline. As a representative of his generation, Larkin expressed the emotions of a man contemplating the end of the road. Anyway, Larkin deserves the fairness of the historian's reassessment for the widespread cultural phenomenon he exhibited: the Tory's typical bewilderment at the immensity of change and decline.

Political correctness

For some readers of poetry it may still be hard to accept that this scholarly poet who was once offered the laureateship by Margaret Thatcher had created most of his work out of a mixture of revulsion, fear and unrequited obsession as he was taking the brunt of postwar modernisation. 2 "The sewer under the national monument Larkin became", which was Paulin's comment on the publication of the Selected Letters in 1992, triggered off a new debate on Larkin (the 'unselected' letters being presumably worse). As Paulin argued, "his obscenity is informed by prejudices that are not by any means as ordinary, commonplace, or acceptable as the poetic language in which they are so plainly spelled out."

3 Any true revolution will have its unsavoury side, and, as Larkin declared in his notorious poem "Annus Mirabilis", "sexual intercourse began / In nineteen sixty-three",

4 sexuality was the battle-ground indeed where the new hedonism became both visible and, to a traditionally educated minority, palpably offensive, at least to people like Larkin, who had, for various reasons, above all, for his art, opted out of the individual's duty to propagation and the family. One might even be tempted to argue that Larkin the sensitive individual distraught with a hedonistic environment is the true sufferer of the new human predicament such as Huxley's grim foreboding in Brave New World. Hardly ever had romantic love been so depreciated as in Larkin's age and in Larkin's poetry or been so absent from poetry devoted to human existence. Any revolution will make visible disruption and discontinuity, which is why Larkin's presumed Englishness is being so unremittingly discussed.

In historical analysis, the changes in sexual behaviour and its public commodification are part of the wider shift of paradigm Western consumer societies rushed through in the 1960s. Accordingly, the issues of sexuality, Englishness and other aspects of the materiality of modernisation are part of the same experience of change, which gather momentum in ever new contexts and situations. Moreover, the national self-image is another significant problem, when some twenty years after his death we have to face Larkin's poetry and the output of the Larkin industry. Political correctness, which will be attacked by any satirist deserving his name, conveys a bulk of repressed attitudes and beliefs. The concept of political correctness suggests that a change of mind worthy of a true revolution can be decreed by the majority in office without any effort beyond that of keeping things unmentionable. In history any fit of collective wishful thinking to bar reality from being perceived, however long it was upheld, has proved ludicrous as it is due to evaporate at a given moment. This state of affairs reminds one of the Victorian age, as hypocrisy seems to have returned to the present political culture. Of course, its major assumption is that the regulation of language will prevent any more serious conflicts from happening. After the publication of Larkin's Selected Letters in 1992 this has become common practice among the righteous such as Bristow who argued, by the way, that Larkin's self-fashioning as the retired poet did not correspond to his awareness of his environment. Bristow rejected the idea that Larkin cannot any longer be appreciated as a "central component of late-twentieth-century English cultural consciousness."5 But whose side are we on nowadays? Historical criticism requires that Larkin's environment has to be taken as a crisis of middle-class culture to which the poet reacted with 'outrageous' outspokenness. To the historian, at least, Larkin's tunnel vision will be the more significant, however dismaying the underlying ideological conflict seems.

Obviously, Larkin presents English cultural awareness from an angle nowadays unpopular and not even acceptable as nostalgia. Heightened sensibility to change may be due to the intellectual's self-centredness. Larkin was unprepared for the change of climate. However disturbing his so-called obscenity may have appeared in his works, in order to catch up with the spirit of the times, he was not the poet ready to indulge in verbal eroticism and in the voyeurism attracted by the mini-skirt, which was the revolution's most obvious gadget. If he were, he would have been unable to question the impact of the revolution and of the benefits and affluence mass society derived from the welfare state. As Paulin argued, "social history and the lyric poem appear to be poles apart".6 The true poet of satire has to face nothingness and the bottomless pit against the tide of the times. Larkin's "ordinariness, accessibility, and then obscenity" thus perfectly match the vulgarity of mass society, whatever Larkin's aspirations to the supposed intellectual elite of Englishness. The coin of political correctness provokes political incorrectness on its reverse, so that Larkin will remain irrepressibly with us. As Bristow rightly concluded, "this poet has certainly not, as the events of 1992 show, entirely disappeared into that abyss."7

The Cultural Revolution

Modernisation brought about a feeling of disruption that was to be called a Cultural Revolution. The term itself was suggested by Arthur Marwick.8 Chopping off heads does not necessarily change a country, when only a few members of the ruling class are substituted. Only a revolution which deserves its name would have imposed the radical changes upon the country which, in the late seventies, a regular visitor to England could have been aware of:

- Material modernisation had many facets, not only in architecture.

- In David Riesman's terms, post-modern society is post-individual and post-liberal. The individual's identity increasingly depends on the patterns of performance provided by the media. 9

- Englishness no longer meant the Empire. The Suez Crisis had dealt a severe blow to British confidence, the more so, as the Empire was gradually dissolving.

- Puritan middle-class society had lost its profile in the context of a welfare state which was rarely granted sufficient means to spread both welfare and advanced health care among the citizens.

- After a few years of affluence, the labour administration was not able to cope with budget problems and inflation during the late sixties and seventies. The British economy lagged behind in the competition with continental Europe, and the French president De Gaulle vetoed Britain's entry into the Common Market. Britain's old economy was falling apart as the beautiful sports cars did for poor quality, which were once the highlight of the British automobile industry, and the trade unions' power and subversive strikes also helped to accelerate the decline of industry.

- The world of the puritan middle classes with their set of values had vanished and was replaced by the materialism and hedonism of a more or less affluent mass consumer society. First of all, owing to inflation, a lot of middle-class savings for old age and other provisions had gone down the drain.

- The generation gap widened after the revolt of the Angry Young Men in the mid-fifties. Youth cult became youth culture which represented the norms of society as a whole. This reminds one of Aldous Huxley's predictions in Brave New World (1932), which was originally conceived as a scathing satire on the American way of life. Swinging London and Carnaby Street are the lasting epithets of the new world created by the media.

- Englishness no longer meant the imperial grandeur of the past. 'Modern' elements of life style replaced class distinctions such as education and language up to a certain degree. However, Englishness did not completely pass away, nor did the class system, but it was to loom large again in a wave of nostalgia at the end of the twentieth century.

The aftermath of this revolution, which severely affected the country in the seventies, was bleak, until Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979. She applied the axe, administered severe cuts on public spending, closed down university departments, cut the trade unions to size, waged a patriotic war against the Falkland Islands and Argentinia, which, as a whole, unequivocally represented a 'Restoration' backlash. While the middle classes had suffered, the hierarchy had still been left untouched. London is still owned by a few aristocratic families and the City as the global capital market had continued to prevail. Nowadays Britain is the largest foreign capital owner in the U.S. due to global capital managed by City banks.

Larkin's anti-modernism

Larkin grew up in a climate the dominant factors of which were his father's enthusiasm for Nazi Germany (visiting the country twice) and post-war existentialism at college with its inherent streak of nihilism. In the poetics of the Movement, after Eliot and Pound and the generation of Oxford dons practising and teaching poetry in the modernist vein, the freedom achieved after the break with the ideologies of the recent past led to a new seriousness and to everyday language which empasized the empiricism it aimed at. Larkin's poetry may thus be infected with the world of "tawdry desires" of the new age which he describes, or, according to Patricia Waugh, "Larkin's poems castigate the culture for its mood of 'lowered expectations', while critics castigated Larkin's poetry for similar effects arising out of his 'less-deceived' mentality".10 Obviously, people tend to punish the messenger for the message delivered. But please don't shoot him for that.

Revolutions are moments of history where the most contradictory movements clash. Modernism was rejected by Larkin, as he declared in an essay reprinted in Required Writing, because it maintained "its hold only be being more mystifying and more outrageous."11 The new rationalism challenged darkness and suggestiveness, however learend Eliot as one of the most intellectual among the poets may have seemed. Beyond Eliot's mysticism of renewable spiritual energies, it would be a foregone conclusion to read Larkin as a post-modernist being aware of the constructedness of sexuality and other variants of role-playing and solipsism, i.e. the tenets of post-modernism, extending over postwar society. Interestingly, the rebellion against the tyranny of modernism was strongly voiced in the fields of architecture as it is there that its rule spread the most palpable dread. Larkin the poet resorts to outrage or sacrilege, i.e. the extremist's emotional reaction. Outrage expressed by the use of offensive language and gesture aims at the highest possible pitch of emotion, which alone may warrant authenticity in the climate of intellectual vacuity described above. Elmar Schenkel passes apt comment on pieces such as "Ambulances" and "The Building" which make visible "die großstädtische Anonymität am Beispiel von Krankentransport und Krankenhaus [...], wobei die mathematisch-funktionelle Raumwelt in ihrer ganzen, den Menschen isolierenden Kraft hervortritt".12 In plain English, the isolation and anonymity are conveyed by the city due to its mathematical-functional spatial order, which is a good definition of modernism in general and of the modern architecture looming as large as Hull Royal Informary, which is the subject of Larkin's poem "The Building" (9 Feb. 1972). Man shows signs of regression when confronted with this trauma of powerlessness.

Source: Hull Royal Informary - homepage

In "The Building" the aseptic modernism of the NHS architecture ("There you see how transient and pointless everything in the world is. Out there conceits and wishful thinking."13 As a landmark of 20th-century progress the architectural 'Brutalism' is unable to allay the poet's existential angst, which the speaker has to go through when waiting to see a consultant.14 The modern building rises out of the suburban environment in sharp contrast and seems to violate the poet's sense of Englishness and of the continuity that is vanishing. Larkin could see the "lucent comb" from his office:

Higher than the handsomest hotel

The lucent comb shows up for miles, but see,

All round it close-ribbed streets rise and fall

Like a great sigh out of the last century.

(The Building, CP)

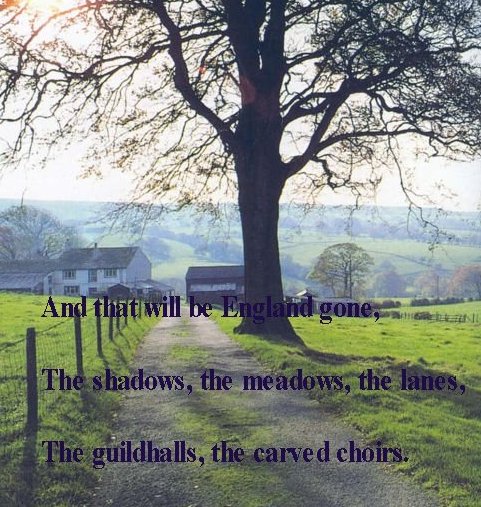

In the same year (1972), Larkin wrote "Going, Going" complaining the impact of mobility and the increasing number of motorists swamping the English countryside while the modernisation of the road network lagged behind. As the "[f]irst slum of Europe" England is left to the mercy of "crooks and tarts" meaning the class of politicians and economists in charge of the country (presumably Labour). The "M1 café" ("the crowd is young in the M1 café") stands for the same architectural design the poet perceives in the NHS hospital. "All that remains/ For us will be concrete and tyres." Merry Old England with its Wordsworthian ring is vanishing:

And that will be England gone,

The shadows, the meadows, the lanes,

The guildhalls, the carved choirs.

The conclusion is entirely appropriate. The poet carries with him, perhaps to excess, a dream of Apocalypse:

[...] but greeds

And garbage are too thick-strewn

To be swept up now, or invent

Excuses that make them all needs.

I just think it will happen soon.

(Going, Going, CP)

Considering the NHS building again, according to James Booth's reading, "the poet seems uncertain whether its grand gesture is heroic or mock-heroic". 15 The sense of bewilderment increases the more the poet takes in the place he first refuses to describe as such which is a kind of wishfully delayed decoding of perception or a failure of repression. Rows of steel chairs stand for the achievement of modernism: its Bauhaus functionality, its sobriety, its deadly rationalism, while the "airport lounge" ironically suggest progress and prestige. But "ripped mags" and "paperbacks" take us back into the squalor and cheapness of modern life. "Angst" is spreading through the breathlessness of Larkin's run-on lines:

There are paperbacks, and tea at so much a cup,

Like an airport lounge, but those who tamely sit

On rows of steel chairs turning the ripped mags

Haven't come far. More like a local bus,

These outdoor clothes and half-filled shopping bags

And faces restless and resigned, although

Every few minutes comes a kind of nurse

To fetch someone away: the rest refit

Cups to saucers, cough, or glance below

Seats for dropped gloves or cards. Humans, caught

On ground curiously neutral, homes and names

Suddenly in abeyance; some are young,

Some old, but most at that vague age that claims

The end of choice, the last of hope; and all

Here to confess that something has gone wrong.

However the poet strove against the perception of the hospital as such, death lies ahead, foreshadowed in the poem's funereal "wasteful, weak, propitiatory flowers". Facing the labyrinthian underworld of this place - ancient myth ("the only coin") and archetype (Hades) looming large - , the individual's sense of time and space and identity is menaced, as the place, however, is not the Greek underworld as suggested but the disenchanted (in Max Weber's phrasing: "entzaubert") world of modernism, or in Tom Stoppard's terms (in Jumpers): the religion being 'rationalised'. Man is obsessed with the tiny budget of time allowed to him. Hence, based on everyday experience, "The Building" is one of Larkin's most haunting and nightmarish poems on the predicament of modern man.16 As Salem K. Hassan remarked when he emphasized the relatedness of the hospital building to the cathedral or church: "Man is here left alone and even God has deserted him." 17 In a way, "The Building" referring to the locked door of the church in the vicinity of the hospital disturbingly echoes Larkin's famous poem "Church Going". A loss of confidence must have occurred in-between, which may be a gain in authenticity based on despair. Moreover, in the face of death, English class society is dissolving, which leaves the speaker with a deepened sense of unease: 18

[...] women, men;

Old, young; crude facets of the only coin

This place accepts. All know they are going to die.

Ulrich Seeber suggested that metaphor, "read in conjunction with the synekdoche 'building', hide[s] a poetological meaning" as an extension of the existential issue for the timeless 'architecture' of poetry. "For whereas the language of poetry overcomes time and death, science and religion apparently do not."19 Is this the meaning of writing poetry in the hospital?

In "Here" the impact of post-war modernisation is felt again. "Swerving east" conveys the rhythm of the train journey; the poet travels back to Hull University, and once again, he converts the boredom of the train ride into what one might call documentary poetry including a glimpse of transcendency or beauty which, as an element of intertextuality, reminds one of Wordsworth's intimations of immortality and evokes London viewed from Westminster Bridge. Even in the North of England, the economy has picked up: "Here domes and statues, spires and cranes cluster". The late fifties finally did not experience the economic miracle of Germany but, rather a spell of affluence after long years of austerity. Cranes signify active life in the harbour area as well as the building industry. The then Tory prime minister Harold Macmillan, who won the 1959 general elections with the slogan "You never had it so good", had been a successful cabinet minister for housing. "Residents from raw estates", however, reveal the speaker's hostile attitude to post-war mass affluence: "raw estates" violate the English middle-class maxim of your home being your castle. American-style "plate-glass swing doors" spreading all over Europe at that time violate the sacred spaces of Victorian and Edwardian architecture. The enumeration of household goods and life-style elements such as "cheap suits, red kitchen-ware, sharp shoes, iced lollies, electric mixers, toasters, washers, driers" stands for American amenities which sweep over Western Europe. Technology and mass production were changing everyday life. The number of fridges and washers and television sets available per household used to be the benchmark for progress and enlightenment in Europe. "Sharp shoes", otherwise called "snail-picker shoes" suggest the vulgarity of lower-class fashion prevailing in a world which the poet tries to scourge with an Augustan, i.e. an early 18th-century English rhetorical figure worthy of Alexander Pope - the oxymoron or contradiction in terms: "a terminate and fishy-smelling pastoral of ships". The joke is that normally you long for terminating yours days in a pastoral among idealised shepherds and shepherdesses. Although the Queen herself wears head-scarves on less formal occasions instead of more or even less imaginative head-dresses, "grim head-scarfed wives" makes the place appear distinctly working-class. So the delicate Oxford poet is scared away from the world as it really is and once again takes to flight longing for "unfenced existence" out of [the] reach of the cut-price crowd." There was once a better past before mass society and affluence - the supposedly true richness of the past and its Englishness: "rich industrial shadows", the presence of the nineteenth century, the Wordsworthian view, the "pastoral of ships up streets", "Isolate villages" of rural England, which was cherished throughout the 20th century, in particular when Larkin was a youth - the last strongholds against modernism.

20

The socially constructed nature of sexuality

Steve Clark remarked upon "High Windows" that this poem "starts out looking like a poem about sex, and becomes a poem about religion".

21 This obvious relationship between the institution of the church and individual behaviour emphasises the socially constructed nature of sexuality up to a certain degree. Discourse on and practice of, sexuality are manifestly changed in the moment of revolution. In the process of social change, the poet on the observation post has to keep his distance, although he will never be able to sever his ties with the maddening crowd. One might argue, with some justification, that alterity is represented by the youngsters as a part of the poet's own repressed self. The problem is that the media society of the present age takes sexuality on the lines of the pleasure principle as seriously as middle-class society did by repressing it under the tenets of the reality principle. "High Windows" expresses the poet's outspoken discontent with the sexual revolution of the sixties.

22 After the Family Planning Act of 1965, which had introduced the free distribution of contraceptives and which Larkin refers to in the first stanza, permissiveness seemed to become widely acceptable if not the norm of human behaviour. Additional legislation concerned abortion (1967), which, of course, was controversial, homosexuality and divorce (1969) and Family Law Reform (1969), which introduced equal rights for children born outside marriage. Sexual standards largely depended on the hold that Churches had on the population. As C.J. Bartlett remarked upon the state of Postwar Britain,"while 'Catholic' and 'Protestant' battled with each other in Northern Ireland most religious denominations in the rest of the United Kingdom continued to lose influence. [...] Morals were being viewed increasingly as a matter for individual choice."

23 In Sex and the British, Paul Ferris obviously sides with the more reluctant among his readers:

The new age of Eros took a few years to dawn. Lurching towards sexual freedom, the British constructed two myths of what was happening to them. In one the nation was maturing, searching its heart, changing its ways. In the other, self-indulgence and anarchy were going to triumph unless there was drastic action. The matter has never been resolved. 24

In "High Windows", the poet likens himself to an "outdated combine harvester", which would be a perfect sample of Eliot's objective correlative the connotations of which one can easily grasp. "Outdated combine harvesters", which represented in the 1950s the breakthrough of modern agricultural technology but which were replaced by more advanced machinery in the sixties, rust away among piles of junk in some neglected farm area. Larkin's sarcasm, intentional or otherwise, reflects a mood of victimization by progress achieved by American companies like Massey Ferguson or Harvester International. This sense of self-deprecation seems to be rooted in the history of his own 'priest-ridden' generation. The association of the confessor as the major factor in his own education implies a feeling of guilt connected with sexual desire and, at the same time, the poet's involuntary severance from faith. And again, the poet's view of contemporary society yields into a vision of nirvana: deep blue air, which is endless, is located somewhere beyond the rising youth cult.

"Annus Mirabilis" takes up John Dryden's famous Restoration poem of 1667. This time, London has not been saved from the Puritan Revolution, the Fire and the Plague, but, ironically, the paradise of the post-Chatterley era is drawing near like "a brilliant breaking of the bank." Human relationships have changed. However, Larkin does not advocate the moral standards of the past. Love with the sole purpose of marriage used to be a sort of blackmail, "bargaining", as he calls it, "a wrangle for a ring, /A shame", life coming never to terms with love. 25 From this point of view, Larkin's bleak message is the one of the "less deceived", the pessimist who falls into a black hole. Moreover, irony and satire are being brought directly to the reader by the diction of the poem imitating the lightness of the Beatles tunes; the poem should be set to music. 26 By the way, the Beatles' first LP was Love Me Do produced in 1962. Pop music became the principal carrier of the new mood. A Beatles historian commented upon the title song Love Me Do:

Crude as it was compared to The Beatles' later achievements, it blew a stimulating autumn breeze through an enervated pop scene, heralding a change in the tone of post-war British life matched by the contemporary appearances of the first James Bond film, Dr. No, and BBC TV's live satirical programme That Was the Week That Was. From now on, social influence in Britain was to swing away from the old class-bases order of deference to 'elders and betters' and succumb to the frank and fearless energy of the 'younger generation. 27

Patriotism

The burden of spreading civilisation was finally to become a vision of the past that is hard to bear. Adapting the country to a future beyond colonialism was a major issue in sixties policies around which nostalgia and pragmatism clashed. "Homage to a Government" echoes famous Kipling poems such as "Recessional" and "The White Man's Burden". By the mid-sixties, British governments had become aware of the dangers and costliness of commitments east of Suez. The Wilson Cabinet had to face "stark realities by the economic crisis from November 1967". "Only then did they make a firm decision to abandon the Persian Gulf and Singapore by 1971 and to give up any specific capability for military operations east of Suez".

28 This move had many critics, but the decision was a realistic one. At that time, apart from the east of Suez part of the former Empire, the African members of the Commonwealth were cutting their ties with Britain. The Empire at the core both of Englishness as national identity and of individual identity was vanishing. English soldiers still secured a minimum of order and civilisation. Under Labour, the budget is poured into the bottomless pit of the Welfare State instead. If the soldiers make trouble happen, this is ironically aimed at a typically left-wing argument against the Empire. One can easily draw a parallel to current affairs: British and American forces in the Gulf region make trouble happen through their mere presence. This expresses the traditional view of the pacifist and idealist public in Western Europe. "All we can hope to leave them now is money" is a withering sarcasm, too. The heroism of the past was at the heart of a radically different set of cultural values. Hedonism and sexual freedom as the desirable goal have taken over.

29 As possible editor of a new Oxford Book of Modern Verse, Larkin ranked Kipling as one of those writers "who have clearly helped to form the twentieth-century poet's consciousness" (20 Jan. 1966). More obviously, Kipling, not yet the reviled poet of imperialism, must have been a set book at school: Kipling preached on the sacrifices made for keeping things "orderly", while Larkin is similarly evoking the protestant ethic of toil for the salvation of one's soul ("We want the money for ourselves at home /Instead of working"):

Take up the White Man's burden--

The savage wars of peace--

Fill full the mouth of Famine,

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

(The end for others sought)

Watch sloth and heathen folly

Bring all your hope to nought.

(The White Man's Burden, 1899)

"Our children will not know it's a different country" which was consigned to oblivion by Labour together with theEmpire and its mission to spread civilisation. In "Recessional", Kipling had warned the English public against giving up themselves, which, according to Larkin, is happening in Wilson's England:

Far-called our navies melt away --

On dune and headland sinks the fire --

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

Judge of the Nations, spare us yet,

Lest we forget - lest we forget!

(Recessional)

To conclude: whether you like Larkin or not, his poetry is built upon the genuine experience of the cultural revolution of the sixties. This experience intensified his conviction of belonging to the "less deceived". His colloquialism might give the impression of a modern poet, but its technical perfection and its impact derive from Larkin's striving to live up to the essence both of English poetry and of Western culture. Hence Englishness as intertextuality and the continuity of English poetry take a prominent role in Larkin's poems,

30 but the reading suggested in this paper focusses on how cultural change puts pressure on the individual's consciousness and on the poet's ultimate failing to cope with it. Many people will recall the sixties as a period of liberation from Puritan restraint and the coming of a betterworld. As a societal construct, the youth cult and its ensuing hedonism would be as palpable as the restraints upon of sexual behaviour prevalent in previous periods. Whatever boundless enthusiasm demonstrated for the new age, the reverse of this coin was decline, e.g. of the Empire and of the old middle-class world of education and politeness. Which, of course, we need not assume to be in contradiction to the idea of liberation, as divergent currents do occur simultaneously in history in particular when the pendulum starts to swing back. Hence, with the historian's benefit of hindsight, the critic at the beginning of the 21st century should be able to keep Larkin's Englishness in perspective.

Works Cited:

- Philip Larkin, Required Writing. Miscellaneous Pieces 1955-1982. London: Faber, 1983.

- Philip Larkin, Collected Poems. London: Marvell Press and Faber, 1988.

- Philip Larkin, Selected Letters of Philip Larkin, 1940-1985. London: Faber, 1992.

- Aldgate, Anthony, James Chapman and Arthur Marwick (eds.), Windows on the Sixties. Exploring Key Texts of Media and Culture. London: Tauris, 2000.

- Allsopp, Bruce, and Ursula Clark, English Architecture. An Introduction to the Architectural History of England from the Bronze Age to the Present Day. Stocksfield: Oriel Press, 1979.

- Bartlett, Christopher J., A History of Postwar Britain, 1945-1974. London: Longman, 1977.

- Booth, James, Philip Larkin. Writer. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992.

- Bristow, Joseph, "The Obscenity of Philip Larkin." Critical Inquiry 21 (1994), 156-81.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, That Was Satire That Was. The Satie Boom of the 1960s. Beyond the Fringe, The Establishment Club, Private Eye and That Was The Week That Was. London: Gollancz, 2000.

- Charlot, Monica (ed.), The Wilson Years. Les années Wilson 1964-1970. Enjeux et débats. Paris: Ophrys - Ploton, 1998.

- Christmann, Stefanie, Ordnung und Konservatismus. Ästhetische und politische Tendenzen in der englischen Lyrik nach 1945. Studien zu den lyrischen Werken von Donald Davie, Philip Larkin und Charles Sisson. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 1998.

- Clark, Steve, " 'Get Out As Early As You Can': Larkin's Sexual Politics." Ed. Stephen Regan (1977), 94-134.

- Clutterbuck, Richard, Britain in Agony. The Growth of Political Violence. London: Faber, 1978.

- Coxall, Bill, and Lynton Robins, British Politics Since the War. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998.

- Davies, Christie, Permissive Britain. Social Change in the Sixties and Seventies. London: Pitman Publishing, 1975.

- Ferris, Paul, Sex and the British. A Twentieth-Century History (London: Michael Joseph, 1993).

- Galle, Étienne, "Dualité, limite, totalité, transcendence chez Philip Larkin." Études britanniques contemporaines. Revue de la Société d'Études Anglaises Contemporaines. Numéro spécial "Philip Larkin". Agrégation (Paris: SEAC, 1994), 71-83.

- Hassan, Salem K., Philip Larkin and his Contemporaries. An Air of Authenticity. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988.

- Jencks, Charles, Post-modernism: the New Classicism in Art and Architecture. London: Academy Editions, 1987.

- Jencks, Charles, Architecture Today. New York: Abrams, 1982.

- Krahé, Peter, "Tod und Vergänglichkeit als Leitmotive in der Dichtung Philip Larkins." Anglia 111 (1993), 59-74.

- Leggett, B.J., Larkin's Blues: Jazz, Popular Music, and Poetry. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1999.

- Lemonnier, Bertrand, L'Angleterre des Beatles. Une histoire des années soixante. Paris: Éditions Kimé, 1995.

- Lemosse, Michel (ed.), Les années Wilson (1964-1970). Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique 10 (1998).

- Levin, Bernard, The Pendulum Years. Britain and the Sixties. London: Pan Books, 1970.

- Ling, Tom, The British State Since 1945. An Introduction. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1998.

- Löffler, Arno, "'Untalkative, out of reach': Die Erfahrung der Natur in Philip Larkins 'Here' und 'To the Sea'". Ed. Günter Ahrends und Hans Ulrich Seeber, Englische und amerikanische Naturdichtung im 20. Jahrhundert (Tübingen: Narr, 1985), 139-50.

- MacDonald, Ian, Revolution in the Head: the Beatles' Records and the Sixties. London: Fourth Estate, 1994.

- Marwick, Arthur, The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy, and the United States, 1958 - 1974. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1998.

- Motion, Andrew, Philip Larkin. A Writer's Life (London: Faber, 1993).

- Nevin, Michael, The Age of Illusion: The Political Economy of Britain 1968-1982. London: Gollancz, 1983.

Paulin, Tom, "Into the Heart of Englishness." Ed. S. Regan, Philip Larkin (1997), 160-177.

- Punter, David, Philip Larkin. York Notes on Selected Poems. Beirut: York Press/Longman, 1991.

- Regan, Stephen (ed.), Philip Larkin. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997.

- Reinfandt, Christoph, "Philip Larkin: Here". Ed. Michael Hanke, Interpretationen. Englische Gedichte des 20. Jahrhunderts (Stuttgart: Reclam, 1997), 309-15.

- Ricks, Christopher, The Force of Poetry. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984.

- Schenkel, Elmar, Sense of place: Regionalität und Raumbewußtsein in der neueren britischen Lyrik. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1993.

- Seeber, Hans-Ulrich, "Philip Larkin's 'The Building' and the Art of Sociography." anglistik & englischunterricht 53 (1994), 51-62.

- Swarbrick, Andrew, Out of Reach. The Poetry of Philip Larkin (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1995).

- Waugh, Patricia, The Harvest of the Sixties: English Literature and its Background, 1960-1990. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.