EESE 4/2005

Herbert G. Klein (FU Berlin):

Paradise regained? - Filming Conrad's Victory as a Means of Coming to Terms with Germany's Past

1 Filming Conrad's novels in Germany

The German tradition of turning Joseph Conrad's novels into films is but a short one. It began in 1931 and the last instance is from 1987 - with practically nothing in between. Both films were adaptations of Victory, which was the first Conrad novel to be turned into a film at all (by Maurice Tourneur in 1919).1 Already the second filming of this novel, William A. Wellman's Dangerous Paradise (1930), announces in its title that it does not pretend to be a straightforward adaptation.2 In this film the happy ending is brought about by "a Japanese servant", who routs the invaders of the island with any weapon that comes to hand. Interestingly, in the light of the following discussion, its working title was The Flesh of Eve. This version was so successful that it experienced five remakes in different languages within two years, including a German version by Leo Mittler called Tropennächte ("Nights in the Tropics", 1930), which was released in January 1931 and closely followed its model. Unfortunately, this film is lost. After this there was nothing for a long time until a French-German co-production of The Secret Agent was shot in 1981, which, however, was never shown in Germany.3. Then, finally, Victory appears again in the guise of Vadim Glowna's film Des Teufels Paradies (The Devil's Paradise, 1987).

The fact that only one of Conrad's novels has been adapted for the screen in Germany is perhaps not very surprising: although Conrad's work has been repeatedly translated into German, his is not a name to conjure with even in fairly well-read circles. Although the reasons for this are of no concern in this context, it may be assumed that a wider German readership for Conrad would have inspired more film versions of his work. As it is, most of the audience of either Mittler's or Glowna's film will not have realised that they were watching an adaptation of a literary work. In terms of film reception in Germany this does indeed make a difference: literary adaptations - at least of highly regarded "serious" literature - are traditionally accorded a certain respect in German cineastic circles. German adaptations of Victory have had to do without this bonus, because critics were usually not aware of the original and its literary reputation.

The question thus arises: why choose this particular novel at all? Why, in the scant tradition of filming Conrad in Germany, is it specifically this novel that has attracted film-makers? In the case of Leo Mittler's Tropennächte the reason was probably just the commercial success of Wellman's film. In the case of Vadim Glowna's Des Teufels Paradies, however, the reasons must be sought elsewhere.

2 Victory into The Devil's Paradise

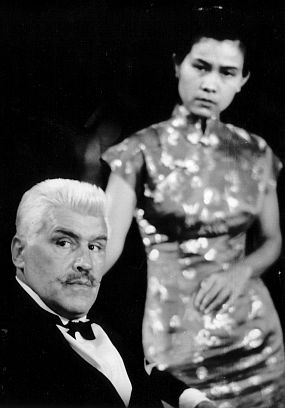

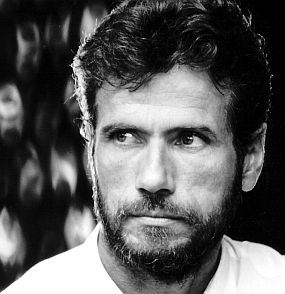

Vadim Glowna's Des Teufels Paradies was shot in Thailand in 1986 and hit the German cinemas on May 7, 1987. Glowna co-authored the script together with Leonard Tuck and Joe Hembus. The film has an impressive cast with an international flair:4 the leading role is taken by Jürgen Prochnow,5 with Sam Waterston as his evil counterpart. Suzanna Hamilton is the leading lady, and Mario Adorf a strong supporting character. Ingrid Caven also puts in a cameo appearance. Apart from these well-known artists, the rest of the cast is less glamorous, at least to a German audience. There are several Thai actors and actresses, who fill supporting roles. One reason for choosing the novel Victory for filming may have been its exotic allure, especially in the island scenes, which apparently appealed to some critics. Although Thailand, the location for the shooting of Glowna's film, was probably familiar to quite a few members of the audience, this does not necessarily preclude its still functioning as a setting for romantic island dreams, but this is certainly not enough of an explanation in itself.

Vadim Glowna's Des Teufels Paradies was shot in Thailand in 1986 and hit the German cinemas on May 7, 1987. Glowna co-authored the script together with Leonard Tuck and Joe Hembus. The film has an impressive cast with an international flair:4 the leading role is taken by Jürgen Prochnow,5 with Sam Waterston as his evil counterpart. Suzanna Hamilton is the leading lady, and Mario Adorf a strong supporting character. Ingrid Caven also puts in a cameo appearance. Apart from these well-known artists, the rest of the cast is less glamorous, at least to a German audience. There are several Thai actors and actresses, who fill supporting roles. One reason for choosing the novel Victory for filming may have been its exotic allure, especially in the island scenes, which apparently appealed to some critics. Although Thailand, the location for the shooting of Glowna's film, was probably familiar to quite a few members of the audience, this does not necessarily preclude its still functioning as a setting for romantic island dreams, but this is certainly not enough of an explanation in itself.

So what was the intended audience for this film? Conrad aficionados, possibly, but it can be ruled out that they were the main target group, since they would hardly have constituted a big enough audience to make the film a box-office success. In order to attract a large enough audience there obviously has to be adventure, love interest and even melodrama, but - given the personality and previous record of the director and main author of the script -one should also look out for more.

3 Contemporary criticism

Turning to the reactions of contemporary critics does not really help to understand Glowna's film, because it seems to have left most of them clueless. An example is Ponkie's review in the AZ:

Je üppiger Glowna die Effekte ins Bild knallt, von den Eingeborenenritualen bis zur Europäer-Tanzbar mit Frauenorchester (Puff-Verpflichtung inbegriffen), desto weniger haben einem diese Kunstfiguren eines Südsee-Melodrams zu sagen. Woran sich also halten? An die dramatischen Bildkompositionen zum Thema Liebe, Tod und Teufel? An das Naturschauspiel der paradiesischen Hölle? Die Bilder sind wirklich sehr schön.6

4 What changes were made to the novel and why?

Of necessity, the plot of the novel had to be shortened and simplified in order to fit the usual time frame of a film. The interesting question - and the one indicative of the director's intentions - is where those cuts and changes were made.

4.1 The plot

An apparently minor change to the novel is the moving forward of the action into the 1930ies - but, as I shall show later, this has far-reaching consequences for the film's meaning. The Devil's Paradise follows a strict chronological plan: there are no flashbacks - whatever little we learn about Escher's past has to be gathered from cryptic remarks or hints like the picture of his father on the wall of the study. (This hint is not likely to be understood by an audience which is not familiar with the novel.)

The first scene of the film shows a procession of native Alfuro girls descending a mountainside in the morning mist. As Escher will be shortly after informed, they are preparing an important ceremony at which strangers are emphatically not welcome. Escher passes this warning on to the only other white inhabitant of the island, Quinn, who, priding himself on his close relations with the Alfuros, blithely ignores it. Escher leaves him in a huff and will later be an aural witness to Quinn's death. Failing to dissuade Quinn from attending the ceremony is Escher's original sin: everything that follows will take its origin from here - Escher's compassion for Julie as well as his reluctance to engage with the invaders of his island. When Escher leaves the island to report Quinn's death to the authorities, he first encounters Jones and later, in Schomberg's hotel, he meets Julie (Lena), who plays in a ladies' orchestra and is about to be sold to Schomberg. Hardly knowing what is happening to him, Escher runs off with her to his island, where they fall in love. This idyll is soon shattered by the arrival of Jones who intends to break Escher's spirit, but only succeeds in finally goading him into action.7 In a lengthy scene dominated by pyrotechnics Escher routs the invaders and leaves the island together with Julie. Jones is left by himself on the wharf and is killed by a shower of native spears.

Glowna thus shortens certain parts of the narrative and, save for the happy ending, he remains faithful to the plot of the novel on the whole. A happy ending, indeed, is something that in the case of Victory each film version (and there have been 12 so far) has found necessary. The only exception being Harold Pinter's script for Victory which stays close to the novel but which yet has to be turned into a film.8 Glowna's cuts and changes to the plot therefore appear to be quite straightforward and mainly serve to tighten the action in order to adapt it to the conditions of cinema.

4.2 The characters

More conspicuous are the modifications to the characters: not only their names, but also their backgrounds are changed. Thus the Swede Heyst is turned into the German Escher. What - one may ask - induced Glowna to this change? There may have been commercial reasons - a German protagonist might lend himself more easily to identification with a German audience - but would this also count with an international audience (and the film was intended for international distribution) and would it really be of significance in a film which is not set in Germany and with an audience that happily accepts protagonists of all nationalities? There is no particular prejudice against Swedes in Germany, and to an international audience this nationality might have seemed more neutral. The name "Escher" is of course immediately evocative of the Dutch artist's self-enclosed drawings and thereby conveys a certain idea of the protagonist's character.9

It turns out, however, that yet more of the characters are turned into Germans. Schomberg, who is already German in the novel, remains so, but he and Escher are joined by the almost the whole ladies' orchestra, including its leader, which all taken together puts quite an unexpected emphasis on German nationality. Film economy often makes it necessary to cut minor characters or to fuse them, but it is also possible to assign new roles to characters or even introduce new ones. Since this is a common feature of film adaptations, I shall only mention those instances where there seems to be a special significance attached to these changes in this film. Glowna actually cut some minor characters completely, rolled some into one, and heightened the importance of others significantly.

It turns out, however, that yet more of the characters are turned into Germans. Schomberg, who is already German in the novel, remains so, but he and Escher are joined by the almost the whole ladies' orchestra, including its leader, which all taken together puts quite an unexpected emphasis on German nationality. Film economy often makes it necessary to cut minor characters or to fuse them, but it is also possible to assign new roles to characters or even introduce new ones. Since this is a common feature of film adaptations, I shall only mention those instances where there seems to be a special significance attached to these changes in this film. Glowna actually cut some minor characters completely, rolled some into one, and heightened the importance of others significantly.

The most important heightening of a minor character is Schomberg who - while retaining his unpleasant characteristics - is given some emotional depth which at least in part explains his behaviour. He is shown to be a henpecked husband who more or less out of despair actually falls in love with Julie and therefore attempts to buy her from Madame - not so much a lecherous act than one of desperation. Apart from making this character more credible, one of the reasons for enlarging his role was probably the fact that one of the best known German actors, Mario Adorf, agreed to take the part. That this actor was prepared to play a relatively minor role shows that he considered the figure to be an important one in the scheme of the film.

Another interesting heightening of importance is the rolling into one of the Zangiacomo couple and casting the well-known singer Ingrid Caven in the role. Apart from the obvious opportunity of showing off her talents, this also hints at a heightening of importance. Since the time-shift to the 1930ies is emphasised by explicit mention of "der Führer", Schomberg and Madame are obvious candidates for the stereotype of the Nazi German who can be quite romantic (although somewhat clumsy) in his or her sexual yearnings, someone who loves music, but can also be quite ruthless when it comes to dealing with the lives of other people.

The counterweight to this group is provided by the Asians who possess a lot more substance and dignity than in the original novel. Only the Alfuros might be said to be "savages" in the old sense, since they conduct moon-light rites and kill anyone who disturbs them.10 Mrs. Schomberg, on the other hand as played by a Thai actress presents a clear contrast to Schomberg himself. She appears to be a much more honest and intelligent person than her husband, thereby subtly representing an ironic counterpoint to the claim for superiority of her husband's "Herrenmensch". While Schomberg clumsily negotiates the handing over of Julie to himself, Mrs Schomberg quietly furthers the relationship between Escher and Julie and prepares their joint escape.

Another female character whose role is heightened in important ways is Mrs Wong. Not even glimpsed in the original novel, she becomes the intermediary between the Alfuros and Escher, friend to Julie and hostage to Jones. In the latter role she provides her husband with the opportunity of throwing some dynamite about, thus setting off the explosive ending of the film. Her several functions can best be summarised as providing a link between nature and civilisation. Her husband, too, is not the uncanny and somewhat devious person of the novel, but rather quite a brave man in his fight against the intruders. The traditional relationship between colonisers and colonised had already been turned completely round, when Escher had to account for Quinn's death to the local authorities, represented by a native civil servant who actually reprimanded him.

4.3 The relationship between the sexes

This is not the only turning around of relationships: as has already become apparent, women play a much stronger role in the film than in the novel. Interestingly enough, Glowna's film actually turns Julie into the pivotal point of the plot: although somewhat passive up to the point when she escapes together with Escher, she then becomes the more active of the two, taking the lead in their relationship, physically helping Jones onto the island (she actually extends a hand to help him up), and finally killing Gato, Jones's henchman, when he attempts to rape her. It is this final act, which seals the relationship between her and Escher by permitting him an unexpected insight into himself.

5 What is German about this film?

The changes that I have described point to a conscious shift in emphasis which stands less for a re-interpretation of the novel than for an attempt to rework it for a different purpose. It appears that this novel lends itself particularly well to being adapted as a means of reflecting on certain themes in German history. The Schopenhauerian strain that runs through the novel has often been remarked on, and Glowna uses it for his own purposes. In the novel, it is only Heyst who struggles with the influence of Schopenhauer's philosophy, but in Glowna's version most of the male characters seem to suffer from it. Not only Escher and Schomberg who are Germans, but also Jones - whose nationality remains somewhat in the dark - might be said to partake of the condition: "Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung".11 In the case of Escher, this is what keeps him from fully engaging with life, whereas it is the driving force for both Schomberg and Jones. The latter especially seems to roam the world in order to shape it according to his own notions: it is a game he is playing, and in a somewhat perverse way he seems to want to lose it. This is why he laughs when he finally finds himself defeated. Escher, on the other hand, rather unwillingly discards his fanciful notions, but when he does, it is also a triumph over the pessimism that his father had foisted on him. Escher's eyes are finally opened to reality through circumstances which are not of his own making. He sheds his illusions about himself and also the destructive influences of his past. The man, whom Jones had earlier referred to as "the omnipresent German whom they call the Enchanted of the Islands" becomes very disenchanted indeed, but he gains a new lease of life.

From this perspective, the contest between Escher and Jones can also be seen in Faustian terms, with Escher playing an unwitting Faust to Jones's plotting Mephisto, who is cheated of the former's soul by the intervention of Julie's Gretchen. (The crucial question of this Gretchen is: "Did you kill Quinn?") Escher is a Faust who does not want to know, because he does not want to run any risks. Gretchen takes on a far more active role: not only does she seduce Faust, but she then also cheats the devil. It is perhaps this reinterpretation of the Faust myth that is most striking about this film.12 Not only Gretchen is there, but also Marthe in the guise of Mrs Schomberg who helps Julie and Escher escape at the instigation of Jones, with whom she has been surreptitiously flirting.

It is in these scenes that Glowna explicitly introduces the backdrop against which this drama is acted out - the Nazi period: on the one side, there are the representatives or at least sympathisers of Nazi Germany (Schomberg and Madame), and on the other their victim Julie13 together with Escher, who does not want to become involved either way. This is the decisive moment for Jones, the force of eternal evil, who enters the scene as a catalyst and slyly arranges the joint flight of Escher and Julie. Jones instrumentalises Schomberg and Madame without their even noticing it. This could be seen as an exculpation of the Nazis: although Jones's intentions are even worse than theirs, the immediate effect is to withdraw the victims from the oppressors' clutches. But what Escher and Julie think is liberty, is only a respite before something worse is about to happen. This something worse, however, can only happen, if they permit it, if they make it possible. Although it acts upon them from outside, it needs their own disposition to collaborate. Jones believes they possess this disposition, because both have been passive in the past: they have not tried to shape their own destinies (Julie laconically explains her presence in the orchestra with "bad luck"). Only if and when they overcome this passivity, will they be able to take their lives into their own hands. What Jones does not foresee is that Julie already starts to be active with her seduction of Escher. It is Eve seducing Adam at the instigation of the serpent, but there is no God to punish them, rather the devil himself wants to take on the job. What the latter fails to anticipate, however, is that Escher has also begun to give up his passivity due to his sexual awakening: the barrier between his Id and his Super-Ego - symbolised by the actual barrier the Alfuros have erected across the island, with their half representing Escher's suppressed desires and the other half the overwhelming presence of his father - is breaking down and he will eventually develop his own independent Ego, symbolised by his departing from the island together with Julie and by Jones's being speared by the natives. And it is therefore not gratuitous that the film starts with the sequence showing the preparation for the Feast of the Virgins: Escher is a virgin himself as far as the realities of life are concerned, and his unwitting implication in the killing of Quinn precipitates him into acknowledging responsibility for his actions. His subsequent conduct is a kind of atonement for the death of Quinn, but he will only be able to clear his conscience by helping others. It is this final recognition that most markedly shows the difference between the novel and the film, since it changes the whole point the novel is making.

To return then to the original question: why did Glowna choose to turn this novel into a film? If the changes he made are anything to go by, Glowna used Conrad's novel for the purpose of coming to terms with the Nazi period and its aftermath from a liberal position in the mid-1980ies. Escher would then represent the German intellectual who becomes guilty through his self-enclosed passivity, his refusal to see what is before his very eyes, above all through his refusal to act. In the film - as opposed to history - Escher does finally act, although it is only because he is goaded into action, and he would be lost, if it were not for the support of the potential victim (Julie) and of the marginalised Other (the natives). It is probably this fact which more than anything else expresses Glowna's position and shows the changes in political awareness in late 20th century Germany: the role of women and coloured people is re-evaluated and strengthened at the expense of the white male. As a matter of fact, almost all white males in this film are shown to be weak and even ridiculous despite (or because of) their self-importance. (An exception is the minor role of Captain Davidson who is played by Vadim Glowna himself.)

Is it then the film's intention to retrospectively overcome Germany's Nazi past with the help of strong women and brave natives? If so, then this gives rise to several questions: Escher and Julie do not really defeat the Nazis, they just escape from them, unless Jones is also counted a Nazi. But is there any justification for this? He seems to act only for himself, he has no ideology but the perpetration of evil, and he takes pleasure in victimising others for no particular end. If one counted him among the Nazis, then this would demonise them and remove them from the sphere of political discourse. Perhaps the film should then rather be seen as an allegory of the development from Nazi to post-war Germany with several themes being interwoven not always quite logically: Escher could be seen as the misguided German who, although guilty of misbehaviour in the past, is able to redeem himself through good works. His heroic endeavours entail not only the destruction of the forces of evil, but also the development of respect for those of a different sex or a different colour of skin, based on the insight that without them he would be helpless. All this contributes to Escher's willingness to break with his past. The film would thus convey the rather consolatory message that, although one may have become guilty once, it is possible to atone for this and begin a new life.

Glowna's film thus seems to be winding its way somewhat uneasily between literary adaptation, adventure story and political allegory. This refusal to be tied to a single message may partly explain the film's puzzled reception, but it may also be a sign of political uncertainty in itself. This could be seen as a reflection of the development of political consciousness in German moderately left-wing circles in the 1980ies, which had left earlier certainties behind.

The original question - why did Glowna choose this novel? - may thus be answered by saying that it seemed to provide a possibility of allegorising a certain German political stance of the1980ies. In order to find a vehicle for his intentions, however, Glowna had to make commercial compromises which imperilled their attainment: the visual appeal of the film runs danger of subduing the political message. On the other hand, in straightening the plot and following a strict chronological order, Glowna made the film more accessible to a larger public than the novel. The happy ending may have been commercially necessary, but it is also justified by the film's oblique message that there is always a chance of leaving the past behind and beginning all over again.

Acknowledgment

Our sincere thanks go to Atossa Film Produktion GmbH (Berlin) for providing the images and for granting the permission for publication in this article.

Notes

1 For this and the following information cf. Gene M. Moore, "A Conrad Filmography", in: Conrad on Film, ed. Gene M. Moore (Cambridge 1997), 224-49.

2 Possibly Vadim Glowna was influenced by this title when choosing his own.

3 The director and the cast were French, the German contribution being mainly limited to the Bavarian film studios.

4 Jürgen Prochnow (Escher), Sam Waterston (Jones), Suzanna Hamilton (Julie), Mario Adorf (Schomberg), Dominique Pinon (Gato), Ingrid Caven (Madame), Tony Doyle (Quinn), Wong Chun-Man (Wong), Atcharapan Paiboonsuwan (Mrs. Schomberg), Vararat Thepsotorn (Mrs. Wong)

5 Prochnow had become internationally famous with his role in Wolfgang Petersen's "Das Boot" (1997).

6 "The more opulently Glowna fills the screen with gaudy effects - from the rituals of the natives to the night-club for Europeans with a female orchestra (including obligatory prostitution) - the less meaning do these artificial characters of a South Sea melodrama possess. What to cling to, then? To the dramatic pictorial compositions on the theme of love, death and the devil? To the natural drama of paradisiacal hell? The pictures are really very beautiful." ( Ponkie, AZ, 1987 [Münchner Abendzeitung])

7 Interestingly, Jones has quite obviously intentionally sought out the island as is proved by his having brought Julie's saxophone - this is quite different from the novel, where it is chance that brings him there.

8 Harold Pinter, "Victory", in: The Comfort of Strangers and other Screenplays (London and Boston 1990), 165-226.

9 Glowna chose the name with these associations in mind (personal communication by Vadim Glowna).

10 In the supposed setting - an island in the Indonesian archipelago - it is just about credible that such a tribe might still be existing in the Thirties. Only a few years ago, a tribe was discovered in Borneo, which had not yet come into contact with the rest of the world.

11 Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Idea (1819; trans. 1883).

12 The fact that Glowna was working with Gustav Gründgens, the famous actor of Mephisto, in Hamburg after the war may be of some significance here.

13 Is it too fanciful to detect the sound of "Jew" in her name? After all, Schomberg and Madame unscrupulously turn her into a commodity.