EESE 8/2007

Global gazes at British Literature

A Report on the 30th Cambridge Seminar

on Contemporary British Literature, 2007

Eva Ulrike Pirker (Freiburg)

In July 2007, forty-six international delegates including myself arrived in Cambridge to catch a glimpse of contemporary British literature. The event which I was about to attend had been described to me by an insider as "the best that the British Council currently has to offer", and my expectations were accordingly high. Indeed, illustrious names such as Andrew Motion, Howard Jacobson, A.L. Kennedy, John Hegley and Jackie Kay graced the programme of the British Council's Cambridge Seminar on Contemporary Literature. The biennial seminar has been a regular event for three decades. With it, the British Council intends to showcase and discuss the UK's "creative ideas and achievements", increase "the number of quality relationships between the UK and many other countries" and establish connections "for the UK's creative and knowledge economy".[1] The institution's approach to achieving these aims is to bring established British writers together with new literary talent and professionals from around the world who work in the fields of publishing, teaching, the arts etc. The following report assesses the past seminar's programme and achievements.

"Coffee break"

Photo credit: Sascha Kirilenko

The seminar opened on the evening of Saturday, 7 July 2007, with introductions and conversation over (very English) Pimms and a dinner at the Howard Building of Downing College. The college is 'only' two-hundred years old; wide green spaces of lawn and early nineteenth-century neoclassical buildings (as well as their late twentieth-century imitations) evoke images of American pendants. The increasingly common practice of selling packaged services to groups that include seminar rooms, lodgings and catering indicates that Cambridge's colleges largely operate as businesses; they are no longer the mythical spaces that continue to attract visitors, students and certainly also some of the participants in the British Council's seminar. However, the good vibes at the seminar were arguably not so much triggered by the setting as by the diverse and interesting make-up of the group. Delegates came from all continents, but the strong presence of participants from Eastern Europe was particularly noticeable. There English literature and culture meets widespread interest and new networks (such as reading groups) are thriving.

In her welcome address, Susanna Nicklin, the British Council's Literature Director, pointed to the role of literature as a vital means of engendering mutual understanding amidst the anxieties and conflicts of our times. Her view was agreed on by most, but also challenged and contested by some in the course of the week, for instance by a writer who maintained that her sole responsibility was the "white sheet" in front of her. The self-positioning of writers in the contested spaces of aesthetics and politics (and increasingly the market) remains arguably one of the most interesting and urgent questions in the study of, and debate on, literature; the Cambridge seminar offered a vast spectrum of new insights concerning this matter.

The first literary event on Sunday morning was a reading and conversation with the poet and biographer Andrew Motion who was introduced by Jonathan Barker (Senior Literature Consultant at the British Council) as a "town-cryer for poetry". Motion said about his role as poet laureate that he felt he "could turn it into a job": his real vocation lies in advocating the reading and writing of poetry, for instance in the poetry archive. Motion read prose and poetry from different productive stages of his life, and the work he presented was based on personal experiences, for instance the famous "Anne Frank Huis" (from Secret Narratives, 1993), written under the impression of a visit to the place in Amsterdam. The autobiographical poems are his strongest as they masterly conjure up universal themes such as death, loss and love. His biographical writing is, as he maintained, a way of writing about others. Nevertheless, the personae Motion writes about are those he "fell in love with" and who have influenced him (e.g. Philip Larkin and John Keats). He opened and closed his reading with the theme of his father, first in a passage from his new prose autobiography In the Blood (2006) in which a scene from his childhood (father and son on a fishing excursion) is conjured up, and then in a poem written after his father's death, a miniature biography ("Wishlist"). Despite Motion's strong presence as "experiencing I" in much of his literature, he is an engaged writer who responds to political events such as the recent war on Iraq. Regardless of its subject matter, according to Motion, "a good poem looks like a glass of water but tastes like gin".

The theme of fathers was taken up again in the next session by Howard Jacobson, author of seven novels and, among other non-fictional works, a book on humour (Seriously Funny, 1997). Jacobson, who is often labelled as a writer of "funny fictions" (chairperson Damian Grant), stated that in order to be able to write a tragic novel he needed his father to die. The reference was to his new work Kalooki Nights, described by Damian Grant as Jacobson's "very own Satanic Verses". According to the novelist himself, it is an "angry book by an English Jew addressed to other English Jews" about Jewish philistinism, the burden of victimship, the duty of remembering and burdensome history. Importantly, the novel also aims to depict the diversity of the Jewish community in Britain; it is literally soaked with Jewish witticism, a vital heritage of the diasporic condition. The novelist maintains that he feels free of the burden of finding a language to write about the Camps. Instead, he described his concern as the search for a new language to write about the shared memory that can become unbearable. Accordingly, the first-person-narrator of Kalooki Nights muses: " 'Remember me,' says Hamlet's father's ghost, and that's Hamlet fucked."[2] Jacobson stressed that no subject is more important than another. Yet once a writer settles on a theme and characters, he has to imagine what it feels like to be another person, for instance an orthodox Jew in the case of Kalooki Nights. In order for the imagination to flow, the writer has to "enter into that other person". Jacobson demands the same of his readers, i.e. that they enter the Jewish English culture and language which he offers them "as a gift".[3] The true fight of his career is "to get humour treated seriously".

After the coffee break, the first of a series of impressive women writers entered the stage: Scottish novelist A.L. Kennedy was introduced by Susanna Nicklin and began by reading a passage from Paradise (2004), a novel written in the first person from the perspective of an alcoholic. Kennedy stated that "we understand ourselves through stories" and that a plot or theme is often the carrier of many other themes. Kennedy was congratulated for her ability to imagine powerful sex scenes, and she commented: "Writing about sex is almost never about sex unless it is pornography." She went on to read from her most recent novel Day (2007), a historical piece about the experience of the Second World War. The novelist expressed particular interest in the exploration of "what a war sets free" in human beings and is convinced that it can bring out the best and the worst in individuals. Day is written in the second person which makes it an intimate reading experience. On the question of what made her write, A.L. Kennedy replied, "It's a sore time - fight or flight." She maintained that writing literature is not only a means of keeping one's sanity, it offers the possibility of "reclaiming in your imagination what has been taken."

The evening session was devoted to a first focus session on Lawrence Sterne's Tristram Shandy: A screening of Michael Winterbottom's adaptation A Cock and Bull Story (2005) was introduced by Damian Grant, and this prepared the group for Martin Rowson's presentation of his graphic novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1996) scheduled for the following morning. Rowson said that his drawings are motivated by satire and that his aim is to expose how narratives work visually. He also maintained that the function of adaptations is either to popularise the original piece or to add something new to it. Like his satire The Waste Land (1999), Rowson's Tristram has become a canonical piece and has obtained a fixed place in Shandian studies. Contrary to The Waste Land, however, in which Rowson settles accounts with the grand modernist T.S. Eliot, Tristram is motivated by his admiration of Sterne.

On Monday, 9 July, the programme continued with Kirsty Gunn, a London-based writer from New Zealand. Water imagery plays a prominent role in her work including the novels Rain (1994), The Boy and the Sea (2006), a collection of short stories and a book of what Gunn calls "things", bits and pieces of poetry (44 Things, 2007). Water and the sea also symbolise the writing process for the author. They represent a "pull into memory" that most often turns out to be a shared memory, a space inhibited by many: "The more particular you become in your memory the more universal you get." Apart from the connecting theme of water, Gunn's subject is family life and the intimacy that can be found there. Gunn reads as much as she writes, and reading is for her a "being at home in the world". The act of creation, on the other hand, is an act of separation: "The minute you've made it it's separate." Gunn spoke at length about her writing method, or rather, the lack thereof: compiling, collecting and writing endless drafts without knowing where it will all lead.

In contrast, the creative method used by writer Rachel Seiffert appears less random, a fact that may be attributed to her training as a film editor. Seiffert read from her novel The Dark Room (2001), a juxtaposition of three narratives set in Germany during and after World War II, and her book of short stories Field Study (2004), which is placed in a more recent Germany and explores the process of the merging of East and West. Her most recent novel Afterwards (2007) features British characters and is an examination of the conflicting forces of distance and closeness in a relationship. Seiffert is devoted to writing about "ordinary people", her maxim being that "there is a poetry in every life." Through the experience of her ordinary figures, however, she negotiates universal themes such as guilt and responsibility.

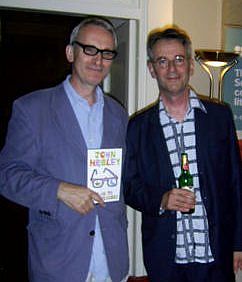

The day's programme was ended with a very enjoyable, yet thought-provoking, performance by comedian John Hegley that centred around dogs, carrots, glasses and other global and local peculiarities. Between songs and poems he spoke at length about his work with children and the way in which drawing and language, images and words, can be put to work for each other. Hegley not only succeeded in making the group sing along but kept some people up for a long time.

"Glasses Exchange:

British Council's Jonathan Barker and John Hegley"

Photo credit: Jonathan Barker

Tuesday was termed 'John Lanchester day': John Lanchester, author of several books, among them a cookbook that is really a thriller (The Debt to Pleasure, 1996) and a family memoir (Family Romance, 2007) was scheduled to read from his work in the afternoon, but was also commissioned to fill the day with a programme and invite other authors to speak. The group agreed that Lanchester's choices were excellent: Maureen Freely in the morning, Sarah Dunant before lunch and a discussion on the future of publishing in the early afternoon. Journalist, novelist and translator Maureen Freely talked about her childhood and coming of age in Istanbul, her undergraduate years at Radcliffe College (described as "defining for her relationship to the USA"), secretarial work in London ("I got sacked from an amazing amount of jobs") and her translation work for people imprisoned in Turkey. Too young to become involved in political activism while in Turkey, Freely said that she realised later that she had been growing up in the middle of a thriller: "Growing up in Turkey and saying you're not interested in politics is like working in the middle of a street and saying you're not interested in cars." Today, she is involved in campaigns for the freedom of expression and is devoted to the translation of Turkish writers. After reading from her translation of Pamuk's novel Istanbul: Memories and the City (trans. 2005), Freely gave insights into her new political thriller Enlightenment (2007). She stressed the strong sense of place in her writing and her ambition to write in many different ways.[4]

Sarah Dunant, former presenter of the BBC's Late Night Show and author of eight novels, also spoke about different ways of writing and the exploration of space, particularly historical space. Her most recent piece In the Company of the Courtesan (2006) is a historical novel set in renaissance Florence. The author explained her desire to write about women in the renaissance, a time of massive cultural transformations, because they "were the voices I was not hearing". She formulated the question that kept her going during the writing process: "When you repress women, how do they express themselves?" Dunant's 2003 thriller The Birth of Venus (also set in Renaissance Italy) and In the Company of the Courtesan mark her gradual move away from the genre of crime fiction, particularly from her successful Hannah Wolfe-series (1991-1995). Dunant said that popular genres such as the crime novel and thriller provide excellent training ground for story tellers but are also a means to capture audiences who might feel intimidated by supposedly "serious" fiction. In the Hannah Wolfe-novels, she succeeded in the "terrible compromise" of keeping her readers' attention and "sneaking socially relevant themes into the genre". Dunant explained her break with Hannah Wolfe by saying that the serial form of writing had become too predictable, both for her readers and herself. Predictability is also a problem in what Dunant described as the larger cultural debates of our times: Should the producers of culture and particularly the mass media "show people what they want or show them something they might want but don't know about?"[5]

This general question still lingered in the air when the future of publishing was discussed by Dunant, Stephen Page (chief executive, Faber & Faber) and Jessica Powell (communications manager, Google). The debate exposed profound changes in the marketplace during the past fifteen years, posing particular challenges to young writers who have to navigate this new battlefield. Writers and readers have not changed as much as the marketplace, as Page stated. Internet publishing has emerged as an interesting counterweight to the traditional book market which is more than ever dominated by mass market players.[6]

Wednesday's programme began with another writer of crime fiction who has successfully operated in the world of publishing for over three decades, Simon Brett. The author of over thirty works (three separate series of detective novels, collections, plays, screen- and radio plays) said - echoing Sarah Dunant - that one can put "about anything" in a crime novel. An advantage of serialised crime novels is the space that can be given to the development of the detective figure. By contrast, Brett stated, it would be impossible to write a literary novel about a single character. Brett spoke about investigative "research lunches" as a vital component of his creative method and about grand literary figures who serve as examples (Austen, Woodhouse, Chandler) and whom he both admires and parodies (for instance in his Faber Book of Parodies, 1984 or in The Wastepaper Basket Archive, 1986). After Brett, the literary biographer Michael Holroyd, best known for his extensive work on Lytton Strachey, entered the stage. Holroyd spoke extensively about his choice of genre and the differences but also similarities between fictional and biographical writing; he maintained that the biographer is a researcher/traveller as well as a creative writer who re-creates and organises the compiled material. The biographer attempts to find a balance between information and imagination (what Holroyed called "the meaningful and the magical", in an allusion to Larkin). Holroyd gave insights into his skills of combining these elements when he read a few grappling excerpts from his work in progress. This biography of the famous nineteenth-century actor Henry Irving is written from the perspectives of several figures around him. Holroyd closed: "I do not think of the reader as I write, but in a sense, I am the first reader."

By contrast, the afternoon programme featured a writer for whom the performative aspect plays a considerable role: Roger McGough is one of the Mersey Sound Poets[7] and was a member of the band The Scaffold during the 1960s and early 1970s. He continues to add to his impressive body of creative work of poetry, drama, screenplays and children's books. First working as a physics teacher, McGough soon decided to enter a full-time writing career; nevertheless, the idea that the sciences and language/poetry can be put to use for each other prevails in his work. In Cambridge, McGough read from a selection of poems from different collections that gave a good insight into his development and stance as a writer: A backward glance at his work is also available in written form: McGough's autobiography Said and Done was published in 2005.[8]

The day's programme ended with a boat tour on the River Cam and a short excursion to local pubs before the closing hour, which is still an "institution" in Cambridge. Geoff Dyer and Jackie Kay, who were scheduled to read on Thursday morning, were already present and many participants enjoyed conversations with the authors. In general, the writers were present beyond their scheduled appearances and joined participants for breakfast, lunch or coffee, enabling interesting conversations in a relaxed atmosphere.

Geoff Dyer made the start the next morning. The writer of fictional and nonfictional books and short texts took the audience on literary excursions to the American desert, the realm of photography and jazz. He shared his admiration of the work of figures such as John Berger and D.H. Lawrence. Both are studied extensively in Dyer's work, Berger in Ways of Telling (1986) and Lawrence in Out of Sheer Rage (1997). A writer who defies generic categorisation, Dyer appeared both distanced and highly self-reflexive. Yet listening to him in this rather quiet session was inspirational. Jackie Kay, by contrast, literally embraced the audience with her words. She filled her time slot almost exclusively with reading and explanations about the genesis of different parts of her work. After a short introduction by Susanna Nicklin, Kay read poetry from her collection Life Mask (2005), for instance "Gone With the Wind", in which she conjures up the film's black mammie's voice, and "Things Fall Apart", a poem about her first encounter with her Nigerian father. Although she addresses difficult, personal and often trauma-charged subjects, Kay is a master of humour; she maintained that humour is for her a means of catharsis and a means of provoking responses to complex things. One of the complexities in Kay's life is her family situation (Kay was adopted by Scottish parents), a subject matter that enters some of her writing. But she also spoke about her sense of having a larger kind of 'extended family' of blues singers. In her prose work Kay evokes fictional figures that leave the reader with the impression of actually knowing them intimately. According to the author, they are very 'real' to her, and in the process of creation they "kind of live with you for a while". Kay is interested in silences, absences, the spaces between the lines, and the agency of speakers. This interest manifests itself in her polyphonic novel Trumpet (1998) about a famous (supposedly male) sax player who, as is revealed after his death, was a woman. According to Kay, Trumpet is an exploration of speech, the things revealed by speech and the way in which voices can be avenues to a different consciousness. Trumpet and much of Kay's short fiction and poetry are about the borderlines between belonging and 'not-belonging'. As the author commented: "I think not-belonging is quite delicious, actually."

The final reading was performed by Michel Faber. To many participants it seemed to be a great privilege to meet this modest persona who lives a withdrawn farmer's life with his wife in the North of Scotland and whose nature does not betray his commercial success as a writer. In only a decade, Faber has produced a considerable body of novels and short stories in unique forms of fascinating and unsettling prose. These works incorporate Gothic elements and create atmospheres of horror and menace. He explores the many facets and implications of sexuality and power and has become a best-selling author since his breakthrough piece The Crimson Petal and the White (2002), a novel of epic length written from the perspective of a prostitute in nineteenth-century London. Urged by readers, Faber 'had to' deliver a follow-up and wrote a volume of back stories around the characters of The Crimson Petal and the White (The Apple, 2006). In Cambridge, he spoke about his mixed feelings with respect to the consequences of his success and read excerpts from different parts of his work, including very promising work-in-progress.

The selection of writers who presented their work at the Cambridge Seminar 2007 gave insights into the wide range and diversity of literature written in the UK. However, some common themes and concerns were discernable. The individual and the individual's quest remain the central concern of the novel, but (auto)biography appears to become increasingly popular as a means of exploring this subject matter. A variation of this general theme in both fictional and factual forms can be found in historical literature that reaches beyond the writer's immediate experience. The range of historical settings and epochs is wide, but a preoccupation with World War II can nevertheless be discerned. On the one hand, new source material and research contribute to a better understanding of this period. On the other hand, the Second World War undergoes a process of increasing mythification since those who have witnessed it are dying out. This strange discursive mélange surrounding historical research and cultural commemoration of the war has proven attractive to a number of established and emerging writers, artists and film makers around the globe ¯ and British writers are no exception. With respect to genre, one can observe a further blurring of the boundaries between what used to be termed high and popular culture: Crime fiction, for instance, has become a form for experimentation and is increasingly embraced by authors who wish to communicate serious themes to a large audience. Yet there are many examples of 'literary novels' that conjure up the lifeworlds and everyday cultures of 'ordinary people' in diverse geographical and historical settings. Almost all authors at the seminar addressed the dramatically changed conditions for writing during the past fifteen years. This subject matter received particular attention from the participants, and one of the most frequently asked audience questions concerned the individual writers' strategies for dealing with the marketplace.

Communication at the British Council's seminar did not flow in one direction: The participants asked critical questions and discussed the issues raised during the readings and presentations over lunch, coffee and sometimes late into the night. Among the highlights of the seminar were the Participants' Readings which took place on Tuesday and Wednesday afternoon. Eleven delegates from the group read from their own literary work, some of which had to be hastily translated in a collective effort: Rukmini Bhaya Nair, Vivimarie VanderPoorten, Pia Juul, Yong Shu Hoong, Eugenia Abu, Pedro Mairal, Alexandr Kirilenko, Stephanos Stephanides, Maha El Said, Shandana Minhas, Rosalind Buckton-Tucker. And, indeed, literature did not stop flowing until the very last minute. A report entitled " Seminar in Rotten English" (in homage to Ken Saro-Wiwa) was written for the farewell party by Damian Grant, and other literary reminiscences were exchanged online. The seminar was competently organised, the chairs and those operating 'backstage' did an impressive job and the non-literary programme was entertaining and well chosen. I feel priviledged to have been part of the event and can only recommend the seminar to anyone interested in British literature and its many contextualisations.[9] Within the British Council, massive organisational and thematic restructuring initiatives have relocated literature and culture to a mostly illustrative, catering function for political, economic and ecological projects. Thus, this seminar is, indeed, one of the last 'dinosaurs' of literary events organised by the British Council.

[1] British Council. The 30th Cambridge Seminar on Contemporary Literature. URL: www.britishcouncil.org/seminars-arts-0701.htm

(accessed Nov 2007).

[2] Howard Jacobson, Kalooki Nights (London: Vintage, 2007), 5.

[3] There was considerable debate among the participants about Jacobson's refusal to italicise or annotate Yiddish words; the author maintained that he asks his readers to consult dictionaries or other sources of information.

[4] Excerpts from the conversation between Maureen Freely and John Lanchester at the Cambridge Seminar can be read on the British Council's website: Maureen Freely and John Lanchester, "Thoughts on Translation", British Council Arts, www.britishcouncil.org/arts-literature-litmatters-maureenfreely-3 (accessed Nov 2007).

[5] Excerpts from Sarah Dunant's talk at Cambridge can be read on the British Council's website: Sarah Dunant, "How The Birth of Venus was born", British Council Arts, URL: www.britishcouncil.org/arts-literature-litmatters-sarahdunant (accessed Nov 2007).

[6] For an interesting article on the relationship between editor and writer in the digital age see: Stephen Page, "Publish or be damned", The Guardian, 3 March 2007, books.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,,2025116,00.html (accessed Nov 2007).

[7] The No. 10 of Penguin's collection of Modern Poets remains the bestselling anthology of poetry produced in England. Adrian Henri, Roger MacGough and Brian Patten, The Mersey Sound: Penguin Modern Poets 10 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1967).

[8] Excerpts from the conversation between Roger McGough and Jonathan Barker can be read on the British Council's website: Roger McGough and Jonathan Barker, "Pop Poetry in the '60s", British Council Arts, www.britishcouncil.org/arts-literature-litmatters-rogermcgough (accessed Nov 2007).

[9] For more impressions from the Cambridge Seminar 2007, see: British Council, "Literature Matters" (Autumn 2007), www.britishcouncil.org/arts-literature-literature-matters-autumn-07 (accessed Nov 2007). For more general information on the British Council's Cambridge Seminar, see: British Council, "The Cambridge Seminar" www.britishcouncil.org/arts-literature-cambridge-2007.htm (accessed Nov 2007).