EESE 4/2007

Nature Choreographed:

The 18th Century Garden as a Knowledge-generating Feature

Anne-Louise Sommer (Copenhagen)

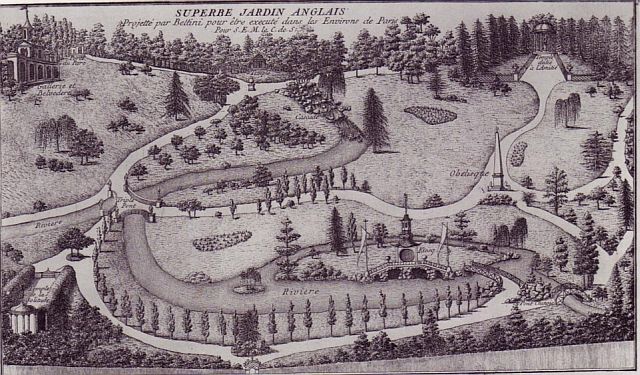

| Fig. 1: Projet de jardin anglais par Bettini – the English influence in late 18th century garden art. An illustration from the highly influential work by G.-L. Le Rouge, Détails des nouveaux jardin à la mode ou Jardins Anglo-Chinois, Cahier XX pl. 4 (1776-1787) - Courtesy SUB Göttingen |

Abstract

The objective of this paper is to revisit the late 18th century landscape garden through a tentative reading of a fictional garden (the description of Julie's Elysium in Jean-Jacques Rousseau's La nouvelle Héloïse, 1761) and an existing landscape garden Stowe in Buckinghamshire, England. The designing of a garden was an essential leisure activity for the privileged, and through this process, space for improvement was materialised. The two gardens will be discussed as a medium for staging knowledge and different concepts of knowledge. Further more it will be discussed to what extent, and through which means, the designed landscapes could provide didactic potentials for the betterment of man.

Finally certain aspects of the obvious hindrances will be discussed when having landscape design and the art of gardening as a research topic and along with that the critical potentials will be put to the fore at the same time. The garden could be regarded as a vision, an image of the world and as such an interpretation of the life-world. As a mental structure materialised the fundamental codes of the culture appears embedded in the landscape garden. This fact opens up for an interpretation through which garden art and designed landscapes could be considered possessing a critical dimension capable of thinking with and against the epistemological systems of a given period.

The 18th century landscape garden: a brief survey

The 18th century was the century of gardens. A veritable craze simultaneously swept over Great Britain, the Continent, Scandinavia and Russia. Influenced by the Enlightenment the gardens addressed a tradition dating thousands of years back in a new way. The ideals were a certain natural touch, as if there were blurring boundaries between the landscape gardens and the surrounding scenery. In general this new concept of garden aesthetic has been referred to as 'the English garden' among many other names such as 'the picturesque garden', 'the informal garden' or 'the irregular garden'. And the contemporary writings talked about the anglomania when referring to this seemingly endless stream of landscape scenes and modes of regarding the landscape as a stage that influenced the garden layouts. It can be questioned to what extent the source of this new garden aesthetic was solely British. The underlying aesthetic ideas for the garden design of the period drew equally on philosophy, literature, painting and sculpture - and there were prolific circles in Germany, France as well as in England.

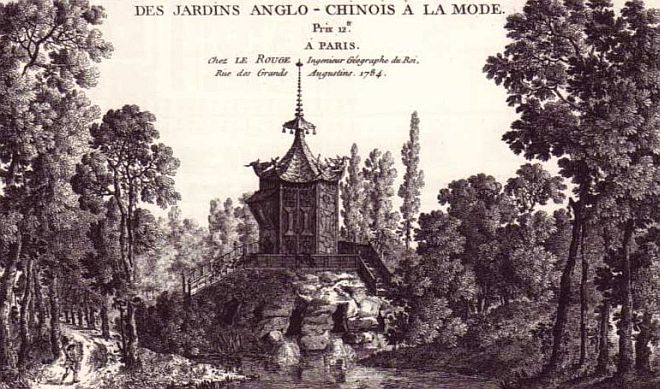

| Fig. 2: "Vue du kiosque de Rembouillet" (Paris); G.-L. Le Rouge, Détails des nouveaux jardin à la mode ou Jardins Anglo-Chinois, Cahier XI pl. 1 (1784) - Courtesy SUB Göttingen |

The title of this paper, "Nature choreographed", refers to the fact that these elaborate and exquisite so-called natural landscape gardens were conceived as 'incarnated nature' and as the epitome of all the best of nature, but at the same time they were the joint product of ingenious gardeners, wealthy landowners and men of taste. In fact these landscape gardens were anything else but the knowingly and splendid staging of the environment according to principles of aesthetic ideals. So what appeared like 'nature' was a highly skilled construction. The notion of the 'natural' is itself a cultural construction, and the outcome of the numerous and divergent interpretations, which have been presented throughout the years, is in itself a reflection of this condition. The paper aims to expose this embedded ambiguity with a specific focus: Namely the potential of the gardens for improving life. To some extent these gardens have been regarded as pure entertainment and leisure activities for the aristocracy, gentry and the economically independent privileged classes, but a closer examination tells us, that the attempt was an improvement not only via pure embellishment but driven by an educational purpose claiming to enhance ways of living, behaviour and moral.

In the following two very different 18th century gardens shall be examined. They are indeed divergent since one is a fictional garden and the other is an actual garden, but at the same time they are both illustrative of different aspects of the complicated and intricate field of 18th century landscape design. As we shall see the scope of Julie's Elysium is the garden as private space, mastered by the intuitive and virtuous gaze, where as Stowe is the garden as public space mastered by a scholarly and magisterial gaze as well as a sensitive one. Together they will be framing different aspects of the designed landscapes didactic potentials for the betterment of man and for the generating of knowledge.

The idealised and imagined garden

Even though fictional gardens or literary gardens never came to a test in real life, they remain eye opening and provide useful resources when reflecting on the outdoor space as a key feature for the general education of all generations. A well-known example of the idealised and imagined garden could be found in the novel "Julie, or the New Heloise", the original title of which ran "Letters of two lovers living in a small town at the foot of the Alps" (1761), by the French Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The epistolary novel has become an extremely popular and repeatedly quoted source to the 18th century concept of 'natural' gardening and nature in general. Even though only one specific letter, part 4, letter 11 to Milord Edouard, relates to this topic,[1] where Julie's Elysium, as she has named her private, secluded garden, hidden from the worldly sphere, is described in all details. The garden occupies an intriguing transitory zone, mediating between the private apartments of the mansion, the semi-public space of the landscape garden and the encircling scenery. The focus is on facilitating the passage from the home to the park, and as such the Elysium could be regarded as an exterior prolongation of the architecture carried through by other means.

| Fig. 3: La nouvelle Héloïse (1761), frontispiece - Courtesy SUB Göttingen |

The capital idea is the impression of a place untouched by human hands. It seems completely unspoiled as nature's masterpiece. In spite of that everything is masterly orchestrated, or as Julie more modestly expresses it: "It's true, she said, nature has made it all, but under my supervision, and there's nothing here, that I have not arranged."[2] Furthermore, art has been a vital ingredient. The tiny paths draw arabesque like figures, and the traces contributes to a graceful choreography, alternating with brooks and running rivulets. The managing of the layout includes everything from large-scale elements such as the controlling of the visual perception of the landscape outline, the staging of the garden as an exquisite space of experience, to the more detailed intervention where all sorts of plants and greenery have been treated like ornamental draping enhancing the overall impression of a combined work of art and nature. All together the elements of nature are consciously modified in order to form a highly elaborate setting, where the outdoors set pieces provides the framework for the sensitive stroll. As Michel Conan has stated, motion is an essential aspect of landscape design[3] and as such Julie's Elysium is no exception. Through movement we engage and oblige ourselves with the world.

In the case of Julie's Elysium the knowledge of nature's transformable potential makes it an important educational project. What appears as a first nature, an untouched virgin landscape, turns out to be a second or even third nature[4] created by a virtuous and sensitive citizen as an important part of the project of cultivating future generations. Julie's husband Wolmar supports this important argument when he stress that the taste for 'the natural' will be intimately linked to the ideal of a "sound soul". There will be much more at stake when considering gardening than pleasure and amusement. Instead of just pursuing art for art's sake and see no enjoyment outside the artificial, the true lover of nature display a unique ability to saunter, to seek out the easy-going and fair promenade. The imagination will be employed, playing together with the grandiose experience of nature. Virtue should be the predominant note in this gardenesque composition. With a reference to the initial, dangerous and subversive love between young Julie and her tutor Saint Preux (The Enlightenment version of the medieval iconic lovers) and the brushwood where their secret and passionate meetings took place. This is constructed as an undisguised opposition between the alluring, out-of-control first nature of the wild brushwood and the well ordered man-made Elysium, appearing like a first nature but never the less a second nature realised by a virtuous woman's loving and skilled hands.

| Fig. 4: Frontispiece Curiositez de la nature et de l'art by l'Abbé de Vallemont (1705) - Courtesy SUB Göttingen |

In a dialectical movement nature can be transformed as well as it can change itself. This makes the Elysium an educational project. Julie explains how "the little ones shall be turned into gardeners" and as long as they participate in cultivating nature they will turn out to be virtuous and sensitive citizens accordingly. The far-reaching influence of Rousseau's writings and philosophy in general in the late 18th century is visible in one of the major treatises on garden art, the five volumes Theorie der Gartenkunst by C. C. L. Hirschfeld (1779-1785), where Rousseau is a truly hero fighting unremittingly against "den falschen Geschmack in den Gärten" ('the poor taste in gardening').[5] And following an extensive quotation from "Julie" it's emphasized that Elysium is "ländlich, gleichsam vernachlässiget und doch reizend" ('rural, neglected, enchanting nevertheless'). Even though Elysium is pure fiction it became a showcase example of the natural garden. It was a point of reference when debating or unfolding arguments. As fictional evidence it was on the one hand a product of an emerging sensibility all ready implemented in existing landscape parks while on the other hand it became decisive in the cementation of the same sensibility, raising it to an indispensable idiom.

| Fig. 5: Hirschfeld, Theorie der Gartenkunst I-V (1779-1785), Zweiter Theil, Zweyter Abschnitt Vom Baumwerk - Courtesy SUB Göttingen |

As a contrast to the so-called natural garden, the Chinese art of gardening is mentioned in Julie, Wolmar and Saint Preux' extensive dialogue in La nouvelle Héloïse. To Saint Preux the Chinese garden represents an extravagant demonstration of power focusing on the wealthy landowners economical capacity as well as culture and the arts obvious command over nature. Where 'the love of nature' seems to be the leitmotif in Julie's Elysium it is the skilful and controlled mastery of nature through artistic means, which is the ideal in China. The so-called natural approach and the Chinese inspiration were indeed two different strategies in the 18th century. And they were both very much 'en vogue'. In France an Anglo-francois-chinois garden style became increasingly popular at the end of 18th century.

The European counterpart to Julie's Elysium is to be found at Viscount Cobham's famous park at Stowe, Buckinghamshire, which is highlighted by Saint Preux as embodying the idea of the simultaneously constructed landscapes materialised at one specific place. Here the visitor finds 'beautiful and picturesque set pieces', a compilation from different countries. Even though the components will be ingeniously put together it doesn't withdraw the attention from the fact that the garden is thoroughly artificial. An elaborate narrative combining different times and places manifested in a single compelling vision. When it comes to Saint Preux' conclusion it is evident, that the intentions behind Stowe are interwoven with the wish to display economical power as well as general education. It lies very far from a desirable mental focus on the virtuous potentials of nature.

It is interesting that when Rousseau wants to make a striking contrast to the idealised natural conditions of Julie's Elysium he chooses one of the most famous and formative English landscape gardens of the 18th century: namely Stowe. Truly Stowe is extravagant in its scope. The garden is a political, philosophical and moral tale in the most literal sense of the word. It is a showcase example of the garden as a didactic landscape. It envisions a project, which goes far beyond the gardens as a wealthy landowner's personal amusement project.

Stowe is an emblematic landscape according to a term coined by Thomas Whateley in his influential treatise Observations of modern gardening (1770). As a grandiose layout Stowe reflects the changing modes and currents of gardening in the 18th century. With a formal garden of a rather modest size as its starting point from the late 17th century, Stowe changed radically and expanded through the first half of the 18th century. In the 1730s and -40s gardener and landscape architect William Kent contributed substantially to the renewal with a masterly choreography with series of picturesque landscapes and a unique staging of the dialogue between framed landscapes of the 'nature' outside the garden, and the cleverly arranged and varied micro landscape scenes of the garden. The Elysian field with references to mythology and antiquity blends with the Grecian Valley and the so-called archetypical English Hawkwell Field. Among the different parts of the apparently natural scenery is spread a wide range of eclectically architectural edifices. Gothic temple structures, a Palladian bridge echoing Renaissance ideals, classical temples bringing alive the classic tradition provides the visitor with different stimulating elements. Numerous visitors, belonging to different social strata, passed by. They admired the landscape, enjoyed a picnic or were engaged in decoding the embedded meanings. As such we might term it an early example of the experience economy to employ a contemporary buzzword.

Today Stowe can be visited and appears pretty much as the original layout was intended in the 18th century.[6] Furthermore we have a unique source to a more profound understanding of the scope of Stowe in a contemporary context in the fictionalised treatise by William Gilpin, a pioneer of the discourse of the picturesque: A Dialogue upon the gardens of the right honourable the Lord Viscount Cobham at Stow in Buckinghamshire from 1748. Gilpin combines the genre of a guidebook for travellers with a philosophical treatise. As readers we are very well looked after. Gilpin takes us literally by hand and leads us through this impressive and vast landscape park. Every single detail is a carefully explained and interpreted within a broad understanding of the past political, societal and artistic context. The chain of reasoning and is staged through a dialogue between two friends: The independent and wealthy Polypthon who likes to travel and to 'visit what is curious in the several countries around him' and the learned and educated young man Callophilus, who has argued extensively that Stowe was worth a visit and therefore undertakes the task providing Polypthon with all the information enabling the full and correct understanding of Stowe as a didactic landscape.

We follow the two friends strolling around the park and their intense dispute arguing pro et con the new modes of engaging with the altered notion of nature and landscape. To Callophilus the garden has gained status as a manifesto, and the gardens becomes an important media for aesthetic as well as philosophical and political discussions. Every time the two come upon a fascinating folly or an enchanting scenery it gives Polypthon the opportunity to inquire: "Do you know the Stories?" and there goes extensive explanations about myths, ancient tales, Ovid's writings and the like while Callophilus provides Polypthon as well as the reader with knowledge and the proper understanding of the landscape. In many cases 'the nature', a rural scene functions as an appetizer, which subsequently will be the starting point for a scholarly reflection. A dialectical relation is described by Callophilus with reference to the countryside: "They contrast beautifully with this more polished Nature, and set it off to greater Advantage. After surfeiting itself with the Feast here provided for it, the Eye, by using a little Exercise in travelling about the Country, grows hungry again, and returns to the Entertainment with fresh Appetite" (p. 50).

The splendid choreography and the general planning of the site, leave nothing to mere coincidence, and provides the visitor with certain fixed routes, which should be followed to attain the most sophisticated level of understanding. A very good illustration of this kind of understanding would be the temple for Ancient Virtues. Here Callophilus explains: "You will meet within a very illustrious Assembly of great Men; the wisest Lawgiver, the best Philosopher, the most divine Poet, and the most able Captain, that perhaps ever lived" (p. 16). With the intention "To establish a well-regulated Morality; to place Virtue in the most amiable Light; and bravely to defend a People's Liberty." In short all these meritorious men serve as role models to the enlightened 18th century citizen as they personify human ideals and virtuous quality. The opposite to these old virtues is a monument in a completely ruinous state emblematic referring to the decayed state of modern virtue.

| Fig. 6: "The Temple of Modern Virtues". Engraving from George Bickham's guidebook The Beauties of Stow (1756) - Courtesy SUB Göttingen |

When coming upon the monument the British Virtues the architectural structure with the different busts placed in each niche tells the story about the 'illustrious worthies', the founders of British society, science and culture. Here the visitors can read devotional inscriptions about the good men's merits and obtain the inspiration to live the virtuous life. The splendid choreography and the general planning of the site, leaves nothing to mere coincidence, and it provide the visitor with certain fixed routes. These routes determine the corporeal as well as the visual movement, all in order to attain the most sophisticated level of understanding. With the termination of the two friends' walk through the garden the dialogue is raised to general reflections about the societal position of the art of gardening. With the possibility of generating the proper spirit for 'the good life', establishing "a just taste" (p. 44) and "advancing the interest of Virtue", the landscape garden is considered a significant feature in public life, even though it might be regarded as leisure activity. Stowe is regarded as a textbook example in stimulating a "Taste for Virtue", and as Callophilus sums up: "In a word, I cannot help imagining a Taste for these exalted Pleasures contributes towards making me a better Man." (p. 46) and Polypthon's comment sound, "Polite Arts improve Virtue! An Affection indeed for a Philosopher to make" (p. 46).

Concluding remarks

Due to this intermediary status, garden art and landscape design can claim to hold, it will be my assertion, that garden art could be regarded as a critical medium capable of thinking with and against the epistemological space of a given period. It would be a privileged space, an empirical order, and "a middle region" as Michel Foucault terms it, when he pins down the position between the already encoded eye and the reflexive knowledge. Following that when Foucault writes about the ability any culture possess for accessing "the pure experience of order and its modes of being"[7] it is a possibility unfolding between "the ordering codes and reflections upon order itself". W. J. T. Mitchell in his 4th Theses on Landscape phrases a kindred issue pointing straight to the complexity of the designed landscape: "Landscape is a natural scene mediated by culture. It is both a represented and presented space, both a signifier and a signified, both a frame and what a frame contains, both a real place and its simulacrum, both a package and the commodity inside the package." [8] Mitchell's point is that it's not important to decide for any of these sharply opposed binaries, which is not possible either. What is important is to confront and address the lag between the two. The landscape garden is interesting as an object of study because it's either a "real place" or a "simulacrum". To some extent, and with a specific reference to Stowe, one could claim that what makes it look like a simulacrum, at the same time is what makes it a real place. Or a heterotopia as Michel Foucault would name it, being one place and all places simultaneously.

The rather eclectic approach one finds in the mode of relating to tradition and inspirational sources in late 18th century garden art could even argue for pointing to a certain resemblance to the post-modern idiom. As a kaleidoscopic imagery comprising arcadic visions, Chinese pavilions, Greek temples and gothic structures the garden is quintessentially cosmopolitan in its expression. Through this vivid compilation an elaborate narrative is comprised with a clear resemblance to an encyclopaedic understanding of the man-made as well as natural world. Willingly, the modern gaze indulges in the abundance volunteered by the garden. The eye being "like a Bee" (Dialogue p. 51) as Polypthon expresses it, and to some extend rebellious in as far as the strategy is a lingering look being "its own Caterer" (ibid.), but at the same time strictly predictable, since this series of 'random' glances turns out to be mastered and subordinated by the underlying choreography. The landscapes designed in the 18th century point to aspects of our contemporary global condition. With the intention of creating a-world-in-the-world as aesthetic reality as well as a didactic display the gardens pushes forth an indeed modern sensibility. When Polypton sums up the concluding remarks after a truly peripatetic walk in the grounds of Stowe, it is with the words: "These Gardens are a very good epitome of the World" (p. 55).

Furthermore, we can conclude that the underlying aesthetic and ethic ideals for the landscape design of the period are complex as well as heterogeneous. The garden can be regarded as both a mental structure and a vision materialised. It's an image of the world and as such an interpretation of the Lebenswelt which, with a perceptible variety, embraces both the nearest and well known and the farthest, both private and public as we saw with the kindred and yet divergent examples of Stowe and Julie's Elysium being emblematic representations of the idea of the garden as public space and the garden as private space. Together they framed different aspects of the designed landscapes' didactic potentials for the betterment of mankind and for the generating of knowledge.

* The original version of this paper was presented at the "Leisure and the making of knowledge in 18th century Europe" conference at Hamburg University, 31st Oct. – 2nd Nov. 2007.

[1] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Julie ou La Nouvelle Héloïse (Paris: Flammarion, 1967 [1761]).

[2] Ibid., p. 354.

[3] Michel Conan (ed.), Landscape Design and the Experience of Motion (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2003).

[4] Cf. John Dixon Hunt, Greater Perfection – the Practice of Garden Theory (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000), chap. 3 "The Idea of a Garden and the Three Natures", pp. 32-75.

[5] C.C.L. Hirschfeld, Theorie der Gartenkunst, 5 Bde in zwei Bänden (Hildesheim & New York: Georg Olms Verlag, 1973 [1779-1785]), I.129.

[6] Enjoy the virtual walking tour by Prof. Tatter (Birmingham-Southern College)

[7] Michel Foucault, The Order of Things – An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London: Routledge, 1996), p. xxi.

[8] W. J. T. Mitchell (ed.), Landscape and Power, (2nd ed., Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2002), p. 5.

Anne-Louise Sommer, Head of Research Department & Associate Professor,

Denmark’s Design School,

Strandboulevarden 47,

DK-2100 Copenhagen Ǿ,

Denmark

Email: als@dkds.dk