Erlangen, 04.12.1996

HGE: Mr Gunesekera, as the biographical information available on you is rather vague, could you please tell me something about your life, especially your relationship with the English language?

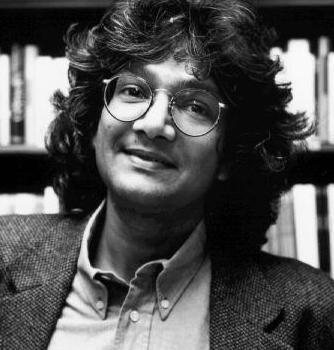

RG: As you know from the brief biographical thing, I was born in Sri Lanka, Ceylon; I think it was then, in 1954. I've spoken English all my life and it's, in a sense, been available to me right from childhood.

HGE: Is it your mother tongue?

RG: No, not really, because it depends how you define these things, but as a child I suppose I was bilingual, Sinhala and English. Maybe you could explain it in terms of that it's symptomatic of history or it's kind of a result of history that you had people growing up who would have English as a first language. They would speak it right from the beginning and be able to speak it right from the beginning, and therefore have a long-term relationship with the language as well. And that's to do with the colonial history, I suppose, of the last 150, 200 years, but in places like Sri Lanka there was much more use of English than perhaps elsewhere.

HGE: Your novel Reef is predominantly set in Sri Lanka, whereas you live in the United Kingdom. Do you see any danger of losing touch with your native country, the country you write about most?

RG: No, I don't think so, because, in a sense, there are two ways of looking at it. One is whether what you write about is a place or whether what you need to be in touch with as a writer, I think, is something inside you rather than something outside you. Which is why, I suppose, as a writer, you write in one place and you're never actually writing about the actual room that you're in or the table that you're writing at. It's always about somewhere else and it is always about a moment ago or two days ago or two years ago or whatever. The distance is a necessary part of the function of writing. It's at a remove and all writers, anywhere, wherever they live, whatever the period they lived in, have always had that sense of distance, and it's actually bridging that distance that is quite interesting. The other aspect, of course, is that, as you were saying, the moment you're going to be doing this online, on the internet, the world is very small, you don't lose touch, everything is, in a sense, much more accessible and closer. And the difference between, I suppose, what is stimulating or what you feel, you could be living in a remote house and somewhere much closer to wherever you're writing about, and still be as distant from it.

HGE: When writing Monkfish Moon and Reef, did you have a particular kind of reader in mind, I mean did you write it specifically for Europeans or Sri Lankans?

RG: No, not really. I think at least the kind of writing that I'm interested in doesn't really demarcate the world in terms of this kind of reader or that kind of reader. The biggest sort of category shift you have, I think, is between people who read and people who don't read, you know, for lots of reasons. I mean, there's a billion people who can't read in the world, because they haven't had the education, they're not literate. But out of the other billions of people who do read, those can be divided into the few millions who actually are willing to read [laughs], you know, all of them are able, but there are only a few who are actually willing to read, and the other attributes are not as significant. Sometimes I do think about who should be reading this and to me the idea is, if I think of the reader when I'm writing, it would be, really, a mind. [laughs] Someone almost like a little cipher on your screen. It's an intelligence, someone who opens a book and gets into it somehow, in a very magical way. Now, at the same time I do know that people who are readers also have a background and also have a physical reality, and they have a set of experiences and they bring all of those to a book when they come and therefore people who, for example, know nothing about the location, the setting of a story or a book, say, Sri Lanka. What they get out of it is going to be very different. What they get out of it is perhaps a discovery of something unfamiliar, but there is a sense of discovery they get, but if they already know the place they get something else. They also get a sense of discovery, but it's a sense of discovery of the familiar, perhaps. So it works in a different way, and obviously, if people know certain things then they will get pleasure from certain sorts of jokes or certain sorts of puns or whatever, what's going on. But they would see similarities or resemblances and so on. And others would see something different. Now, it becomes more different; after the first book, the second book, or the next book, it will change, because then you do know some of your readers, because you do know some people have read the book, and what happens then is a kind of developing relationship, which is why, when you read someone's book, you then read another of their books and there's a deepening relationship, because you have a shared area as well as an unknown area.

HGE: In Reef, Sinhalese expressions are incorporated into the English text as if it were the most natural thing in the world, most of the time without explaining the word. Is this the conquest of the English language and thus the perfection of the former colony's liberation?

RG: [laughs] Some people have written to say that, yes, certainly. I think it's true, it has to do with how the language works and how a language is refreshed or made dynamic. You can interpret it lots of different ways. You can interpret it as a conquest on one side. It could be the other way round, of course, that the language is actually incorporating this and feeding on it as much. In a sense, it doesn't matter which way you look at it. What's interesting is the dynamic that's going on. To me, it's subservient, really, also to the art of the novel, and given the characters who are talking, given the kind of immediacy of a story for the person who's telling the story, the narrator, then it is perfectly natural that the language goes in this way: this is the language, this is the register that's going to be used. If there were explanations all along, to me there would be no point to it, because the function of it is slightly different, it isn't the sort of pseudo-cleverness in the past, when people would want to incorporate different languages into a text simply to make it more inaccessible, or, to sort of say, "Really, if you want to read me, you ought to be educated in such a way, so that you actually know all the classical languages and you're well-read in at least 15 other languages" [laughs]. To me, that isn't interesting, that's obscurity, it is cleverness, it is kind of exploitative. To me, it's much more a question of actually trying to give a texture to the language, trying to give a sense of how it works. For example, in Reef, those expressions come partly at the same time as the narrator Triton is going through his story and is becoming more and more self-aware and more and more rooted and make him identify himself more and more with his past. So it becomes more and more important for him. And he's finding his voice and he's finding that his voice is going to be different from the voices around him. It's going to have a peculiar and unique mixture of things.

HGE: As it is often the case with German translations, the foreign expressions used in Reef are explained in a glossary. How do you feel about that?

RG: It's difficult for me to, in a sense, handle it, once you've moved from one language to another. Not knowing German, I can't tell. And obviously, in a translation, there are limits to what you can do. The exploration that I'm doing with the English language is difficult to then carry on. You can approximate towards it, I suppose, in another language, but that may happen with using perhaps English expressions rather than twice-removed sort of expressions. So I think it's a very difficult one and I haven't really thought much about whether that's sensible or not. I know there have been translations where people have felt it's necessary not just to give a glossary but to actually give a bit of a footnote to say that this is there because of some political event that had taken place which people may not know. I mean, some publishers would find that important and they know their readership, I suppose, but to me, I think books don't really need a lot of explanation. I think they need to work on themselves. I would like to know what other people think, whether a glossary is useful or not. I would suspect that if you can read it in English and not know what some of these words mean but actually make up an idea of what it must mean, even if it's wrong or right, it doesn't actually matter. It's a mixture of sound and you build up your meaning for words, it makes you use imagination in a certain way.

HGE: Yes, as you read in Reef 'kolla' and you have no idea what it means, and after some pages...

RG: Yes. I mean, 'kolla', for example: that's there very early in the book, it doesn't mean anything, people don't know how to pronounce it, it could be Latin, for somebody else it could be very, very different. But then you realise that it's something and the change, I suppose, is going back to this relationship of who is reading and so on. People who know the expressions, for them it's very clear, they get an (laughs, claps his hands) immediate hit of that. People who don't will have to work out something. But it means that if I've written stories since then which I published in which I again use the same word, but knowing that if someone has read Reef, then if they happen to read this other piece, they will get a slightly different kind of flavour. They will get something out of it, because they'll recognise the word, it becomes part of our shared vocabulary. To me, that's very exciting, that kind of thing.

HGE: Even though most of Reef takes place in Asia, allusions to The Tempest or telling names such as 'Triton' rather suggest a connection to Western literature and mythology. Would you say that your works are more rooted in Asian or European culture?

RG: To me, I think, in a sense, it's useful to separate cultures at some point, and there are obviously mythological systems, but I think in 1996, most people sort of know something about everywhere else. Most readers, anyway, know something about everywhere else. They've known it for a long time. If someone was reading a book in English in Sri Lanka 60 years ago, the chances are they would know a huge amount, much, much more than most of us now know about Classical Greek Mythology, because that would have been part of their education system that they would have gone through. So it's slightly false when we start thinking that somehow these areas are separated and that they have separate kind of mental constructs around that, because they don't, and they haven't for a very long time. It's convenient to think that they do, but actually they don't. If you read even very, very traditional writers from different parts of the world, writing in a bygone era, you know, before we had cyberspace, [laughs] before we even had Hollywood, before there was any kind of mass culture, even then you would find that someone writing in a very, very different environment, whether it's in Asia or whether it's in South America or whether it's in Africa, they would still have a sense of the culture of the world. Because that is, in a sense, the engagement you have. You know, even when the Greeks were writing, they had a sense of the culture of the world. Maybe very limited and of course they didn't know a lot of things, but they approached it as if they did. And now, none of us actually know any more. It sort of varies. For most of us, I suppose, our education is such that it's actually become much more fragmented and we know very little about lots of different things. Culture is not contained, it's all over the place. And therefore what I write, I also draw from whatever interests me. If you think about it, really, if you get something out of the idea of the power of the word, now that you find in any system, if you like. 'Triton' is one example of it, in Greek Mythology, of the power of the word, the power of the voice. You get it in Christian Mythology, the word, the flesh, the whole business of people, early Christians chanting certain words because it gives a certain mysticism, a certain spiritual whatever-it-is. And you get in other parts of the world. You get it in Asia, the important sacredness of the word, getting the right word, the mantra. So you can find it everywhere I think, really, and what's interesting is using all of that together. And also, these days, if you write a book and if it gets read in different places, you already are moving very quickly into a different area.

HGE: What are your major philosophical influences?

RG: Ummm...[laughs] difficult one to answer, actually. I'm very interested in philosophical thought, both Western and what has traditionally been divided into Western or Eastern, or then big divide between Continental philosophy and British philosophy, empirical philosophy. I don't know whether there's any one philosopher or school of thought that I find dominant. I suppose the basic questions don't change very much. You see it very clearly in the whole argument about Plato, it's about what is good. It's a definition of what is good - seems to be pretty fundamental to anything. [laughs] "Are we dead or alive?", you know, the very existential ones - to me, they are always kind of current and important.

HGE: When speaking of imagination, is there any specific notion that you favour?

RG: Give me an idea of what sort of notions you are thinking about.

HGE: Well, like, say, Bacon's notion that's it's something negative or Coleridge's notion...

RG: I'm not sure whether I can sort of lock it into anybody else's idea of it. I think what Coleridge says about imagination strikes a chord with me, I think that makes sense to me. I suppose I look at it in perhaps more practical terms as to what do I mean or what do I try to do with imagination, and to me, the imagination is the pulse that keeps us alive. You know, it's almost the kind of parallel to medical science you might have. You know, if there are sort of electric impulses in your brain-stem, then you're still alive. I don't know if there's a connection with the electrical impulses and the imagination. I wouldn't recognise electrical impulse if I came across it, because I wouldn't know how to recognise it unless someone gave me a little computer screen and said, "When you see these, that means there's an electrical impulse going on", but I do when I come across imagination. Somehow I sense it, and to me, that is actually what keeps us alive. So to me, it's a very vulnerable, sensitive element of our make-up, but it's fundamental to it.

HGE: Do you think that Reef has elements of elegy in it?

RG: Yes, it has, because, in a sense, if we go back to what we were saying a little earlier on about writing about place and what I was trying to say is that writing is always at a distance, it's always not about something immediately. It's the difference between Van Gogh painting the chair, you can paint the chair just there (points to a chair) and you can sit in front of it and paint it. You don't do that with writing. You don't sit in front of it, you don't get hold of someone and say "You sit there and I'm going to write about you and describe the features for my character". That's not the way it works. It's always about something elsewhere, out of sight, something in the imagination. And that means that the distance is, I suppose, very important. Distance is important and therefore distance is physical, geographical, if you like, whether it's inches, feet, metres or kilometres or thousands of kilometres. It doesn't really matter, that's just relative. Whether we are talking about something that's happening upstairs in one of those [hotel] rooms unseen or whether that room is on the other side of the world, in Japan. It really doesn't matter, it's far away. The other way is through time, whether it happened yesterday or a hundred years ago. And in both of those, what, in a sense, connects the two is the sense of loss or the sense of not being there, which again, I suppose, might come back to a more existential sort of discussion, but it's that sense of loss and when you look at loss, that's where, in a sense, the elegy comes into it. So it's one of the threads that seems to be there in any writing, but in some writing it might become more important. And I think in Reef, yes, it is, it's about the passing of time, it's about the fact that time passes. [laughs] It may be a very good thing that time passes, but it's what you do about it.

HGE: Are you in touch with any other contemporary writers?

RG: These days, again, I think, it's difficult not to be in touch with other writers, because there is a much more public aspect to writing. There are lots of literary festivals and lots of occasions on which you do meet other contemporary writers. So, 'in touch' in the sense of, yes, I get to know them. But, paradoxically, I think, with that, there's probably less likelihood that you have schools of writers as there was in the past. It's almost as though, I think, in the past, where there was less public platform and there was less opportunity for people to meet, you may well get writers who get together much more and, in a sense, develop a school of writing whatever. But now it seems to always, in a sense, work the other way, actually. You get to know lots of people, but actually do your own thing.

HGE: Are there any German authors that influenced you?

RG: 'Influence', I don't know. I mean, I suppose, everything you read influences you in some way. I'm not sure I could really put a lot of names to it. And 'influences' are not always necessary, it's more a question of what interests you. You know that someone is interested in trying to do some kind of thing with their work, they're interested in developing it in a certain way, and that, I suppose, it takes someone like Günter Grass and the sorts of books he's written, they interest me. Influences can be positive or negative, but it's more a question of whether you come across them or not, really, and out of younger writers, I don't suppose I have read that many. I've read occasional pieces in anthologies and so on that I've come across.

HGE: Triton's turkey is a sort of Western packaging full of Sri Lankan stuffing. Do you see any parallels in your work?

RG: I suppose it is, because, in a sense, it's there symbolically as well as a kind of confluence of cultures and how it can be brought together and what stays apart, as it were. And obviously, in the book, it serves lots of different functions, including the sort of business of how these cultural differences are handled and whether they're brought together or not and who does it. As it turns out, Triton is the one who actually produces the thing and he is perhaps the least sophisticated of the characters there, just as, in a sense, the artist may not necessarily be the most sophisticated, but may well be the one who can integrate lots of different things.

HGE: The special significance of the culinary art in Reef reminded me of the 'chutnification' of history as it is done in Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children. How would you describe the role of cooking in your work?

RG: It's there in the stories as well, but in Reef it actually does have a significance. You might almost say if you talk about history as chutnification, the equivalent of what's happening here [i.e. in Midnight's Children] would be, I suppose, cooking is doing to, I don't know, maybe to the theory of art what chutnification did to history. To me, that's what it's trying to deal with, it's trying to deal with ideas of how you value art, how you produce it, what's the impulse to create it, what's done with it, what are the elements in it. It can serve as a kind of parallel to look at books and the way a novel might be produced and compare it to the way a dish might be produced. Two people can produce, can use the same ingredients, basically the same techniques, may even actually follow the same recipes and end up with two completely different-tasting things. So all books actually, all novels, share certain elements with every other novel. I mean, they're basically made out of words, they basically follow a certain pattern, sentences, they basically have characters, they can be very, very surreal, but nevertheless have a kind of character, they have a certain logic to them, and yet they'll be very, very different, and some people will like a certain kind and some people will not like it. And even if they're very close together. Even if they are very similar in the sense that, I don't know, somebody else writes a book about a servant or writes a book about a boy growing up or writes a book about a cook. It could follow a very similar pattern and yet be totally different in terms of the experience it gives you. Just as you eat lasagne in one restaurant [laughs] and lasagne in another restaurant, and one's bad and one's good, one tastes this way and the other tastes the other way.

HGE: Do you regard Triton's development as a positive one or is his story one of failure to overcome the old relationship of master and servant, thus resulting in a negative development?

RG: I kind of leave that open, really, open to interpretation. I think, ultimately, is has to be a bit of both. It is positive, I think if he hasn't found release, if you like, by the end of book, end of that period, if you like, the real-time period then he would have found release by the end of the book by articulating it. But whether the whole thing is positive or negative kind of depends where you're coming from. Triton, in a sense, demonstrates what it takes to survive these days. Whether you think that Triton at the end of it is sympathetic or not, because you could find Triton perhaps less sympathetic at the end, because he's no longer the person he describes in the book, actually, he's a different sort of person, and whether the world that he now has to inhabit, whether that's a positive one or not. It kind of depends on whether [laughs] you're in that world or not. It seems to me it means to be open, which is why I think of it as an artistic work rather than, say, a philosophical work, because, in a sense, it has to leave it open. That, to me, is part of the function of it. If it's closed, then it would fail.

HGE: When writing, have you any expectations or hopes of achieving something politically?

RG: No, I don't think so. I think there are polemic writers and there are writers who write to achieve certain things, but you write a different kind of work, I think. I mean, it's partly this idea of what is political. In a sense, everything we do is a political act, there is a political dimension to everything. To me, what's important, I suppose, with fiction, is kind of reviving values of being able to look again, look freshly at something, not to prejudge it, I suppose, to catch yourself if you are actually beginning to condemn things without looking at what it is you're condemning. It's a kind of mutual reaction. So that's a limited area, I think, that you're working.

HGE: Does the praise you received for Reef put you under any kind of pressure concerning your future output?

RG: No, I think praise is very nice to have, it's much better than having the opposite of it [laughs]. I mean I've been writing for a long time and, in a sense, the first books had come out at the end of a long period of writing and the pressure that you bring to bear in writing actually has its source somewhere else, not really in the expectations of other people. There is obviously a bit of pressure, but that can go either way. In a sense, it's almost part of another world. It's good that you have praise, next time you may have praise, you may have condemnation, next time after that, you won't know, so that, in a sense, doesn't matter. Writing is, I think, a very difficult thing to do. I find it very difficult. And I have enough problems trying to write something to my satisfaction anyway. I don't really think I have time to be worrying about the rest of it [laughs].

HGE: Finally, may I ask what you are curr%ntly working on and where it takes place?

RG: I'm always trying to write a story. I never really talk about what I'm writing because I find that impossible to do. Writing, to me, is actually a way of living, it's a way of thinking, it's a way of discovering, it's a way of actually getting from today to tomorrow, and therefore I can't sort of preview it and quite often I really don't know where I'm going until I get there. It's a bit like getting into a car and driving and if someone asks you "Where are you going?", you say, "I'm just going somewhere over there." [laughs], but once you get there, you know that that was where you were going, actually. And you know perfectly well what's in front of you, every inch of the way, but you don't know the whole thing. It's a process of exploration, it's a process of understanding and thinking and trying to understand where you are, where the world is, where we're all going. All I can say, I suppose, is it's another novel, I'm writing another novel which should come out fairly soon. Where it's set? I mean, like I was saying last night, Reef started out as something completely different, so I don't how the other one will go, but there'll be a link with the other two books in a some way.

HGE: Thank you very much for this interview.

I would like to express my thanks to several persons and institutions for making this interview possible, apart from Mr Gunesekera himself. Firstly, the British Council, especially Marijke Brouwer (Cologne) and Stephen Ashworth (Munich), Brigitte Drescher of the Unionsverlag, Zurich, then Prof. Dr. Rudolf Freiburg and the Erlangen Centre for Contemporary English Literature (ECCEL), Sabine Hagenauer, and Rosemary Zahn for proof-reading this interview.

The copyright and all associated rights for this interview remain with Romesh Gunesekera. Anyone wishing to reproduce it in any form should notify the British Council.